The Difference Between Art and Life

, r)Life-experience obviously inspires arts of all types: dance, cinema, sculpture, painting, etc. Some art forms are clearly differentiated from mundane experience, while others exploit the convergence of art and life (we call this verisimilitude) as essential to a populist appeal.

In the first decade of the 21st century, a new form of television entertainment emerged known as “reality TV,” which purports to offer the viewer extraordinary unrehearsed experiences of nonactors. Settings are often “exotic,” but the participants are chosen because they appear “mainstream.”

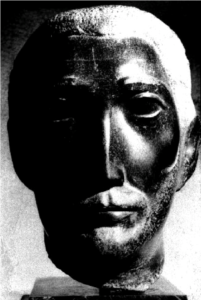

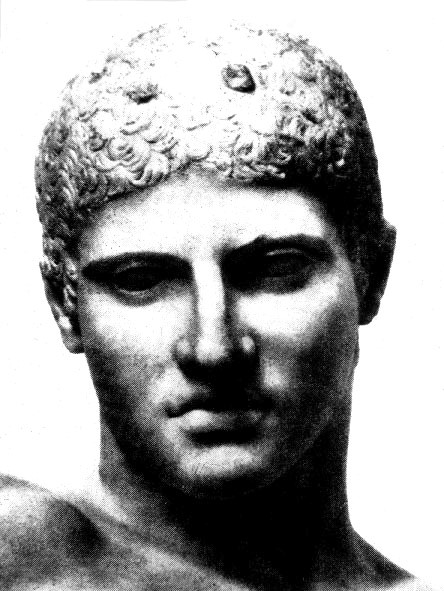

Maillol experimented with “leaving out” anatomical elements of his Liberty Enchained (Fig. 6-3, right) in the analogous Torso (Fig. 6-4, left), thus virtually achieving qualities of plundered Greek antiquities.

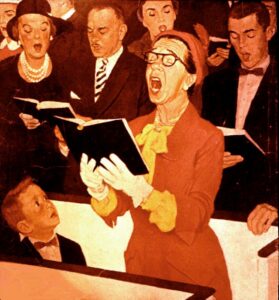

Such forays into “real life” are not new to the art world (witness the compelling pathos of Norman Rockwell’s mid-20th-cen. Saturday Evening Post cover in Fig. 6-1). Heated discussions on the relative value of “illustrative” art and “fine art” often focus on merits of “photographic likeness,” obscuring a more fundamental truth embedded in the tension between art and life.

In a later Chapter (10), we will explore subtleties surrounding terms such as “Realism,” “Fantasy,” and “Surrealism,” but success in that enquiry may very possibly hinge on prior agreement as to the role of verisimilitude in the human art-making process.

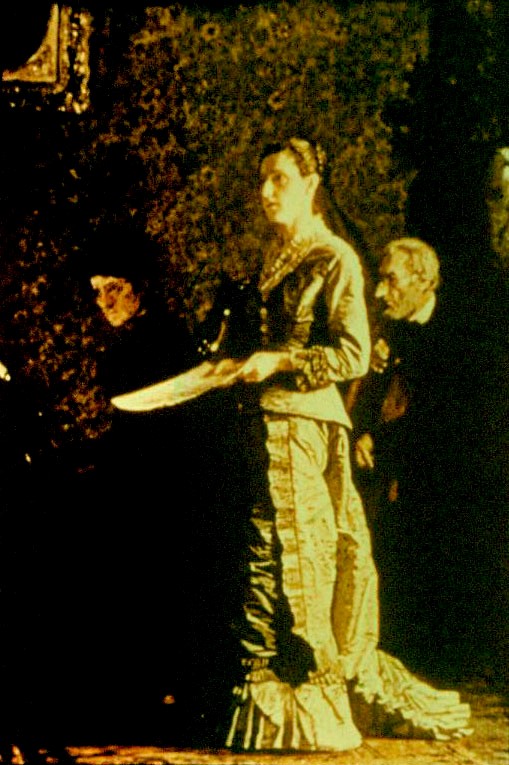

In contrasting Thomas Eakins’ rendering of an aspiring singer (Fig. 6-2) with that of Norman Rockwell, it appears that Eakins was not as interested in “personalities” of his principals as was Rockwell, whose task, after all, was “newsstand appeal.” Eakins seems focused on dramatic subtleties of light-and-shadow (a preoccupation of Romantic artists since the time of Caravaggio and Rembrandt), rather than on the transient psychology of figures in his gloomy Victorian interior. Drama here (in the Eakins), arises from what is obscured rather than from what is described.

Greek Goddess, Aphrodite from Melos, (Fig. 6-5, 6-5a, right) appears balanced and confident without arms, while later Venus de Medici (Fig. 6-6, left) betrays self-conscious “modesty” of conception with full array of limbs.

A similar comparison of sculptural works by Aristide Maillol may shed more light on this tension between art and the descriptive impulse. Maillol produced a bronze figure entitled Liberty Enchained (Fig. 6-3), which appears to be a metaphor of French political aspiration. Subsequently, however, the artist divested the figure of all extremities (Fig. 6-4), and reproduced just the Torso in a bold reduction of descriptive information provided to the viewer.

Such radical departure from an original lifelike image of Liberty to its truncated essence as a “mere torso” would seem to suggest a process at work. In much the same respect that Eakins’ work distills the heavy-handed reportage of Rockwell’s magazine cover, Maillol tempers his own political idealism with a straightforward diminution of anatomical detail.

This reductive process can, as we shall see below, take many forms: a denial of verisimilitude in terms of space (ie. as in relief, as opposed to sculpture in-the-round), in terms of time (producing immobility, for instance), in terms of emotion (psychic distance), in terms of form (voids communicate also), in terms of medium (paint, stone, fabric replace subject-matter), or in terms of content (latent meanings can transcend the obvious subject-matter.)

Each art-form has its own reductive language for signifying the difference between an artist’s creative statement and the human experience which validates that art form. Western theater, for example, is always conditioned by some type of performance-arena, by lighting effects, by choreographed movement, by dialogue. Traditional Japanese theater relies on a different set of conventions (masks, for example) to effect separation between theatrical experience and daily-life beyond.

Doubtless we’ve all heard the expression: “Less is more,” and ravages of time and history have offered myriad examples of “damaged” masterpieces to underscore the point. Such a work is the famed Aphrodite from Melos (Fig. 6-5) a Hellenistic Greek stone figure which lost its arms sometime after its production (before 200 B.C.) With her confident contraposto stance (the S-curve effected by throwing weight on the rear foot) and unwavering gaze, this semi-nude figure appears ever the Goddess. A comparable but later figure (Fig. 6-6, 1st cen. B.C.) known as the Venus de Medici (for it’s early Renaissance owners) has all its extremities, yet makes the viewer feel uncomfortable because the arms appear to conceal her body as if in embarrassment.

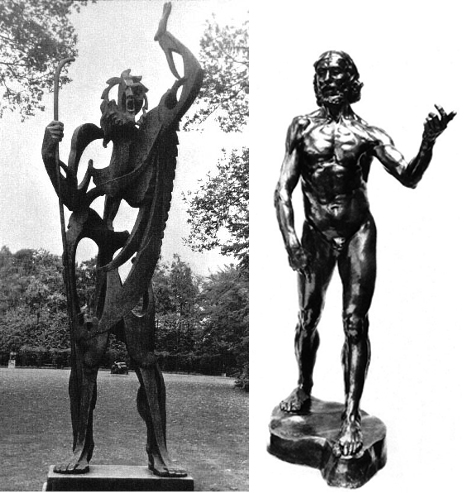

Prometheus and the Eagle by Jacques Lipchitz (Fig. 6-16) suggests explosive pneumatic energy which distances this bronze form from the naturalism of Rubens.

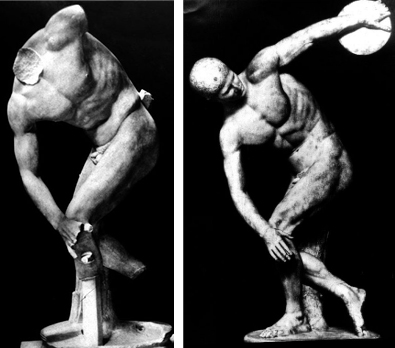

Classical antiquity gives us another such anomaly in the modern “reconstruction” of Myron’s famous Discobolus, popularly known as the Discus Thrower (450 B.C.). Originally discovered in fragmentary form seen in Fig. 6-7, the marble sculpture was subsequently “reunited” with a head deemed by archeologists to have been part of the same unfinished Roman stone copy of Myron’s bronze original. (Stone-cutter’s temporary reference points, known as a boss, appear side-by-side on the marble head.) Later, a “throwing arm” was added, along with a discus, hands and a left leg, below the calf.

Opinions will rightly vary on the outcome, but one might conceivably argue that the damaged version more successfully conveys the “essence of athletic movement” than its “reconstructed” precursor, by virtue of the accidental elimination (reduction) of all but the pith at the center of the concept. Whereas Myron had contained his athlete’s energy within an implied circle, fragmentation made that unity “latent” rather than explicit.

Reductive process is evidenced by comparison of works by 17th cen. painter, P.P. Rubens (Fig, 6-10, The Three Graces, left), a sculptured work, The Three Graces (Fig. 6-11, center) by Maillol, and “semiabstract” Three W omen in stone (Fig. 6-12, right) by Henry Moore.

One can directly experience the “stripping-off” of layers of verisimilitude in comparing Ruben’s treatment of his painted image of The Three Graces (Fig. 6-10) with two sculptured versions of the same subject-matter. Ruben’s sensuous Baroque style obscures little of the visceral detail of the figures or their surroundings: natural flesh tones and lush vegitation create palpable reality. Maillol, on the other hand (Fig. 6-11), has reduced flesh to bronze, and unlike Ruben’s animated figures, Maillol’s Graces effect a “classical” disinterestedness. Though both the Maillol and Moore treatments are in three dimensions (hence life-like), their immobility and the obdurate quality of their materials distance them from human experience.

Bird Formation by Berthold Schweitz (b. 1908) captures exhilaration of space and-movement (Fig. 6-20, left), while Brancusi used artifice of stone-cutter (Fig. 6-21 after 1912) in poised, static form of Yellow Bird, marble, right.

Moore’s Three Women (Fig. 6-12) are said to have been described by a contemporary critic as “gutless pin-heads” when they were installed in a British park. And surely it may have been difficult for a public accustomed to admiring Greek masterpieces of the Golden Age at the British Museum to accept these stone icons as canons of beauty in the mid-20th century. Absent facial features, cultural “markers” of any substance, even significantly “feminine” characteristics, these stone monuments perhaps have more in common with Stonehenge than with the elegant Parthenon goddesses in the British Museum. Each viewer will possess his or her own threshold in this departure from “life” as we know it, but the remarkable discovery one makes is that the further the artist ventures from verisimilitude (without losing “connection” with us), the more satisfying it is to revisit the work again and again.

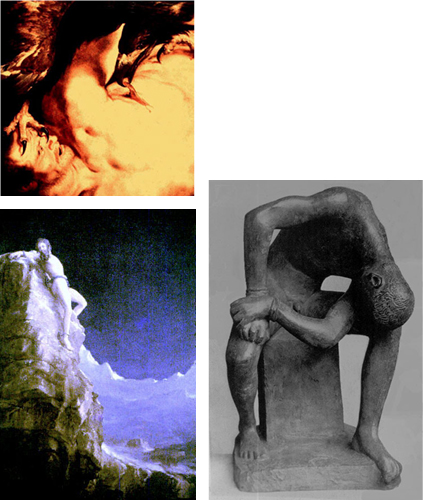

Take for example the suffering of Prometheus: Rubens gives us a visceral image of the eagle plucking at his liver (Fig. 6-13 is a detail, 1612). More than 200 years later, an American, Thomas Cole, sought refuge from the “truthfulness” (verisimilitude) of Native landscape painting in an “ideal” recitation of the same mythology. A detail of his rendition in Fig. 6-14 depicts a metaphoric hero manacled to a visionary mountain in the distance. The mythic eagle can barely be found in the Cole painting, and resembles a turkey-buzzard more closely than a Rocky Mountain predator. Cole in effect has reduced the grizzly tale to a Hans Christian Anderson bedtime story.

Early 19th cen. “allegory” by French artist Canova (Fig. 6-26, marble) described Pauline Borghese as Venus. (1808)

The German scupltor, Gerhardt Marcks, in 1948 saw the epic drama of Prometheus in terms of an immobile bronze figure evidencing despair, minimal physical constraint and a lack of individuality. (Fig. 6-15) Muscular tension invites our engagement in the drama here, to be sure, but “sculptural values” such as tactile geometry of the figure reassure us that this is “art” not “life.”

An even greater departure from verisimilitude can be experienced in the rendering above by Jacques Lipchitz from the steps of the Philadelphia Museum. His Prometheus and the Eagle (Fig. 6-16) though cast in bronze at one-nineth the size of an original architectural version, conveys an almost “pneumatic” sensation (of energy pressing outward from within). Muscles, cape, half-throttled bird all express the plasticity of modelling-clay — a medium typically used in anticipation of the bronze-casting process. In addition, Lipchitz conspicuously alters the pathos of the situation, putting Prometheus in control, rather than the eagle.

Perhaps it would also be helpful to witness this reduction process in regard to a specific artist. Many great practitioners, including Rembrandt, Daumier, Manet, Matisse and Picasso (to name a few) found solace in simplifying their style. At one moment, we see Picasso experimenting with a life-like “Monumentalist” or sculturesque style in a 1921 oil (Fig. 6-17, Mother and Child). Three years earlier, he had tried “breaking down” similar forms of his Woman with Crossed Arms (Fig. 6-18, 1918) into flat planes of a Cubist image, and eventually, his Girl with Necklace (Fig. 6-19, 1944) is reduced to bare profile line, without relying on either chiaroscuro or color to enhance verisimilitude.

In a low-relief panel just 3-ft. high, Jacopo della Quercia condenses The Creation of Eve (Fig. 6-33, marble, right). Leo Steppat’s Rearing Stallion (Fig. 6-31, left) is made of forged iron with startling equine power.

At the risk of belaboring this phenomenon of art moving away from life, I would like to touch on another form of reduction, from mobility to immobility. Then we can speak of the retreat from psychology (pyschic distance) and the reduction of pathos.

Bird-flight has always held a fascination for mankind — a metaphor of speed-and-freedom which animates the design of aircraft, and lately, even the automobile. Sculptors have employed the tensile strength of metal (Fig. 6-20) to titillate our vicarious pleasure at seeing a flight of birds pass overhead (Schweitz uses bronze here). Alexander Calder later developed the “Mobile” to actualize kinetic energy in a precisely-balanced metal construct, now familiar to museum-goers.

For Brancusi, however, the essence of birdflight was apparently invested in the sleek, projectile form of space vehicles (Fig. 6-21) long before the first V-2 rockets were launched toward the British Isles. In this Romanian artist’s imagination, it was evidently the potential of propulsion that was a distillation of kinetic experience, rather than the actualization of flight in a covey of birds. Appreciation of the Brancusi design (also rendered in stainless steel), requires a leap for the uninitiated perhaps, but its rugged economy of language invites one to savor a tactile summation of a normally visual experience.

Michaelangelo develops a visceral, three dimensional Bound Slave from Marble (Fig. 6-34) following his first episode working on the Sistine ceiling.

Similarly, in Figs. 6-22 and 6-23, one discerns a movement away from nature in the comparison between Paul Manship’s bronze Europa, and the linear (bronze) construction by Mirko Basaldella, simply entitled Bull (1948). Manship’s bull is frozen in a moment of ardor, abducting the object of its desire, while Basaldella gives us only a timelapse impression of menacing aggression as head, neck and horns sweep from ground-level to airborne in what looks much like a clutter of bicyclehandlebars. Understatement appears to be the objective in the latter work, and we are left to participate in the creative process to the extent we are able.

Rodin, oft-criticized for his zealous adherence to anatomical verisimilitude, portrays John the Baptist Preaching (Fig. 6-25/1878-80, bronze) with virtually the lifelike presence of a wax museum. To properly grasp his motivation, one must surely consider the “Classicized” (ideal) marble figures of the previous era (Fig. 6-26, Canova, 1808) which Rodin reacted against, as well as his links with the “scientific” thrust of Impressionism.

When Pablo Gargallo designed The Prophet, in 1933 (Fig. 6-24, bronze), it is also reasonable that he created voids and decorative geometry to relieve the pathos of his religious zealot. This was not a period when the “church militant” was seeking to inspire its faithful with dramatic imagery as it had in Gothic and Baroque times, and the reductive impact of secular Cubist Style had begun conditioning Western taste away from natural, descriptive forms.

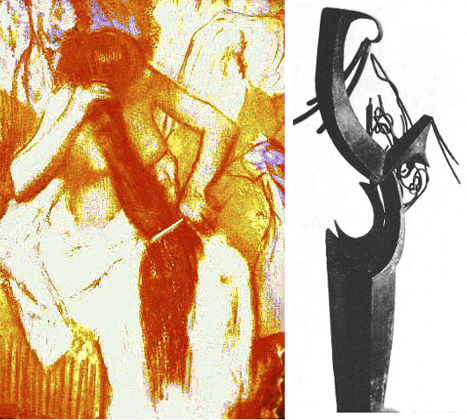

This conditioning is also manifest in comparison of a work by Degas (Fig. 6-27, Woman Combing Hair) with a sculptural statement made in 1936 by Spanish artist, Julio Gonzales (Fig. 6-28, Woman Doing Hair, bronze). Degas “differentiates” his subject from the mundane by an astute plastic arrangement of the woman’s arms, hair and gown, while Gonzales virtually eschews “reality” altogether by fabricating his figure of “bits and pieces” of metal, and eliminating salient features such as the head and shoulders.

To this point we have seen the artist utilize reductive processes involving content, mobility, form and even choice of medium. We should add to this list manipulation of space and the attenuation of time. (One often hears reference to the “timelessness” of early Egyptian forms.) And perhaps even more importantly, the artist must ultimately refine raw emotion into art before it finds its way into museum or cathedral.

Rendition of Menkaura, a 4th-Dyn. Egyptian Godking, (Fig. 6-36, left) trancends worldliness in quest for eternity, much as does Whistler’s famous Arrangement in Grey and Black (Fig. 6-37, right)

The German sculptor, Edwin Scharff, is in some ways more eloquent in the restricted language of low-relief sculpture (above, Fig. 6-29) than “in-the-round” (Fig. 6-30), despite truncating the hind-quarter of the latter animal to amplify its ties with heroic antiquity. The exquisite lyricism of motion conveyed in Scharff’s relief also eclipses the propulsive energy of Leo Steppat’s free-standing Rearing Stallion (Fig. 6-31, forged iron) and invokes the aesthetic power of low-relief sculpture which informed painting and sculpture of the Early Renaissance after Giotto and Masaccio. (Fig. 6-32)

Renaissance sculptor, Jacopo della Quercia likewise employed low-relief in his monumental rendering, The Creation of Eve (Fig. 6-33, Bologna, 1425-38), venturing to portray a powerful Humanistic vision of God more than half a century before Michelangelo’s epochal rendering on the Sistine ceiling. However, ironically, when Michelangelo himself carved an over-lifesize Bound Slave (Fig. 6-34) between 1513 and 1516, for a pope’s tomb, he chose to depict the figure virtually in the round, creating a convincing musculature and “reduction” purely in terms of studied “classical detachment” of his unfortunate captive. (Possibly a metaphor of the sculptor’s own servitude to the papacy.) In that brief 75-year period, the pendulum had swung dramatically toward verisimilitude, and it would not be until a 20th century reaction to Rodin that Western sculptors could once again embrace “unclassical” modes of expression with “builtin” signals that art was a departure from reality. Ernst Barlach, for example, carved his small scale Man in Stocks from wood in 1920 (Fig. 6-35), leaving no doubt in the viewer’s mind that this was an artist’s outcry against human cruelty. One can also see the bite of Barlach’s chisel on the wooden surface — a constant reminder of the painstaking carving process. (In some instances, his carvings have been replicated in bronze, creating the anomaly of a “casting with a carved look.”)

Maillol’s Mediterranean (Fig. 6-38 ) mixes pyramidal frontality with Classical reserve to transcend worldly description. (Bronze, 1902)

As with Barlach’s Man in Stocks, his Old Woman Dancing (Fig. 5-60, 1920) has a stoic reserve characteristic of the artist’s best work. Like his countryman, A. Durer, whose dancing peasants we have seen earlier (Fig. 8), this German artist instills emotion with more than a little melancholy.

In contrast to Barlach’s empathetic emotional portraits, one must juxtapose a sizeable number of artistic statements which appear to “arrest time,” and in the process, avoid altogether those ephemeral psychological states with which we easily empathasize. Conditions that produce this effect are hard to categorize, but among the earliest practicioners of this “timeless” genre were 4th-Dy- nasty stone-carvers in ancient Egypt. (Fig. 6-36) With their gaze lifted above the mundane plane and a relaxed immo- bility, these stone figures maintain a stance known as “frontality,” which renders any “casual view” out of the question. Whistler adopted such an iconic pose in his famous 1871 portrait of his Mother (Fig. 6-37), and we discover something of that same majestic quality in Maillol’s metaphoric paean to Classicism, The Mediterranean. (Fig. 6-38) It is balanced geometry mixed with a contemplative mien which anchors this bronze image in a tradition of “timeless” humanistic idealism.

Egyptian God-king, Chephren (Khafra), Fig. 6-42, right, has “transcendental” aura, while wood-carving, Madonna and Child (Fig. 6-41, left) by Robert White, utilizes gesture and glance to place figures in an “existential” context.

Among modern sculptors and painters the aspect of “timelessness” has not resonated as widely as it did among ancient carvers of the Mediterranean. One such votary of permanence, however, was the American artist, William Zorach, whose stone Head of Christ in Fig. 6-39 and Cat carved from Swedish granite (Fig. 6-40) convey much of that universality which informs the 4th-Dynasty portrait of Chephren (Khafre) Fig. 6-42. Not all such eclectic efforts result in “distancing” their subject-matter from a mundane, temporal quality, however, as can be seen by comparison of Chephren with Madonna and Child by Robert White (Fig. 6-41). The latter carving creates static frontality, but without the ethos of eternity. It is here, at last, that we enter into the realm of psychology, which we will investigate next in Chapter 7.

Norman Rockwell's Saturday Evening Post cover (Fig. 6-1, top) and Thomas Eakins' painting, Pathetic Song (Fig. 6-2, above), utilize similar visual tools to capture and retain viewer's interest.

Myron's bronze (copy) Discobolus (in Roman marble before "reconstruction" (Fig. 6-7, left) and after (Fig. 6-8, right), evidences fortuitous "reductive" process. Stone-cutter's "points" appear on brow of "found" head, below. (Fig. 6-9)

From Rubens' 17th cen. Prometheus Bound (detail, Fig. 6-13, above left) the retreat from verisimilitude leads to Thomas Cole's 19th cen. American treatment (detail, Fig. 6-14, left) and Marcks' 20th cen. sculptured version (Fig. 6-15, right).

Picasso's retreat from life-like quality seen in Fig. 6-17, top, or analytical planes of Fig. 6-18, above, culminates in economy of line-drawing of woman's figure (Fig. 6-19, right) entirely devoid of color or chiaroscuro.

"Frozen bronze" captures varying degrees of implied mobility in Bull (Fig. 6-22, top) by Basaldella, and Europa (Fig. 6-23, below) by Paul Manship.

Life-like anatomical detail and polished bronze characterize style of Rodin's 19th cen. John the Baptist Preaching (Fig. 6-25 right ), whereas 20th-cen. Prophet by Pablo Gargallo (Fig. 6-24, left) exploits spatial distortions to emphasize departure from life.

Woman Combing Hair, by Degas (Fig. 6-27, pastel, left), relies on plastic geometry to transcend the "illustrative," while Gonzales' Woman Doing Hair (Fig. 6-28, right, 1936, bronze) utilizes metalic fragments to "suggest" womanhood in search of elegance.

Low-relief sculpture by Edwin Scharff (Fig. 6-29, Horse Monument, 1929, above ) relies almost exclusively on ambient light and water tumbling on thin copper (sound) for its power, while the artist's Torso of Horse (Fig. 6-30, top) effects ethos of "Greek antiquity," spindled by pylon and absent limbs which provide motive force.