Apples or Madonnas?

Another very basic issue we encounter when looking at “unfamiliar” art is the question of subject-matter. Is a painting or sculpture especially important because it deals with a topic of particular significance?

When painting first became a major focus of artistic energy in European society, it was widely believed that the principal subject-matter should be religious rather than secular. That emphasis on “eclesiastical importance” created a legacy which is still with us to some degree.

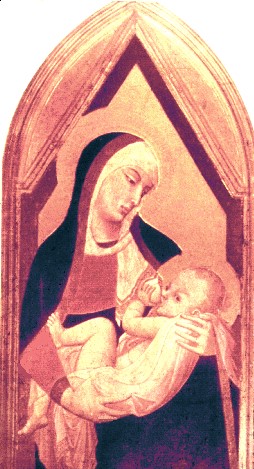

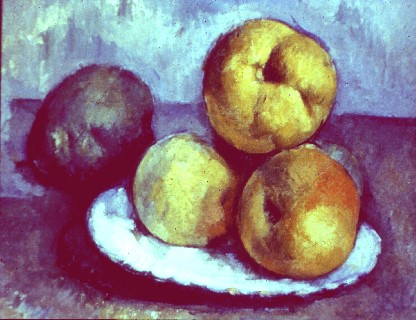

Such a legacy of religiosity makes it more than a little difficult for the uninitiated viewer to look at Cezanne’s 19th-cen. painting Still Life with Apples, (Fig. 1-15) with the same solemnity he or she brings to Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s 14th-cen. Madonna (Fig. 1-16). Yet, if perfectly candid, many viewers would probably admit the apples are more satisfying to behold than this particular Virgin.

How then is one to establish notions of artistic value in the face of radical disagreements concerning subject-matter? Obviously, there is another consideration involved here — the element of aesthetic experience. We must balance the significance of subject-matter against enjoyment the artist furnishes our senses: richness of form, texture, color, line or pattern.

The term aesthetic refers to experience of our sensory apparatus: vision, touch, hearing, smell or taste. We can scarcely divorce our perception of artistic meaning from the level of sensory excitement a work generates in us.

Cezanne set out to make his fruit as palpable an image of sensory richness as paint-on-canvas could create. He manipulated warm and cool colors (along with light and dark values) to create forms that were as solid (tactile) as we can visualize them. The resulting image for some viewers may signify the “fecundity of Nature,” while for others it expresses just the rich color and form of ripe apples.

Lorenzetti, on the other hand, embodied his faith in a moving icon not designed to stimulate senses of his viewers so much as to edify them spirituality. Much painting of his time was done on plaster walls where an alkaline “ground” subdued colors, and besides, patrons were in most cases commissioning works for the “glorification of the Virgin,” not for the glory of the artist. Later, discovery of the glowing brilliance of tempera paint being used in Flanders enabled artists like Simone Martini to create rich “religious” imagery which compares well in sensory power with some of Cezanne’s.

A strong tactile component characterized Giotto’s later works, such as the Angel of the Uffizi Madonna (Fig. 1-17, left), also influenced by Byzantine piety of his master Cimabue (Fig. 1-18, right/ detail of St. Francis Santa Trinita Madonna, Assizi.)

Students of 13th and 14th century Italian “primitives” may find added satisfaction in the Lorenzetti piece due to a developing tactile quality introduced by the master Giotto (Fig.1-17) or an enhanced Byzantine richness engendered by Cimabue (Fig. 1-18). But most uninitiated viewers would probably experience more immediate satisfaction from the dynamic aesthetic qualities of Cezanne’s apples (Fig. 1-19). Indeed, nobody should feel embarrassment in acknowledging their preference based on sensory excitement. It is not irreligious! In some instances, the aesthetic aspect is more critical than choice of subject-matter.

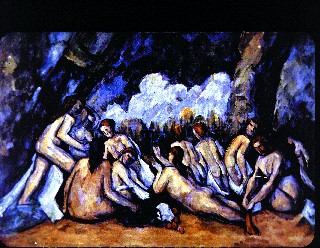

As a further illustration of the tension between sensory experience and subject-matter, it is interesting to compare some of Cezanne’s apples with the same master’s human figures in his Les Grandes Baigneuses#, 1900-1905 (Fig.1-20). As we are cultural products of the Humanistic Revolution (the Italian Renaissance), we would certainly expect to feel strong preference for the artist’s image of bathers as opposed to mere fruit! But do we? Perhaps not. Close scrutiny of the figures portrayed in Fig. 1-20 reveals a highly synthetic treatment of human anatomy — a kind of “wooden” quality suggestive of “imagination” or apriori formal doctrine rather than first-hand experience. Cezanne was a shy man who lived in cloistered surroundings with his wife — circumstances not always conducive to study of nude models. How then could he familiarize himself with subtleties of the human figure?

From an aesthetic point-of-view, Cezanne’s apples have a directness, an experiential intimacy which his figures lack. Frequent studies of stilllife objects, like his oft-repeated images of Mont. St. Victoire (Fig. 1-21), gave him unique power to transform these natural objects into convincing color and form on canvas. Unfortunately, the same ring of experiential integrity (in my opinion) is not present in the nudes (cf. Fig. 1-22). Cezanne sought to “bring Poussin back” into painting, after Impressionism had replaced Neo-classical geometry with ephemeral aspects of visual experience (light, movement, surface effects). But for Poussin, the human figure was primary. Cezanne, attracted by certain “formal” canons of Neo-classicism (such as its search for geometry and balance), ultimately felt called to paint the nude, although, unlike his contemporaries Rodin and Renoir, he had little opportunity to experience unclothed models in repose.

In this case, subject-matter did play a role in determining aesthetic power, but the ultimate stature of the outcome does not seem to hinge on religious or even Humanistic values, but on the intimacy of the artist’s vision.

Personal experience of Figs. 1-15 ( Still Life with Apples,19th c.) by Cezanne and Fig. 1-16, ( Madonna and Child, 14th c., above), by Lorenzetti may be arbitrated by different criteria: sensory or religious.

Fig. 1-19 &1-20. Cezanne's capacity to convey "firsthand" aesthetic (sensory) experience appears stronger in a detail of Apples (1890-94) than in his later nude human figures. ( Les Grandes Baigneuses, 1900-1905, above).