Communication or Expression?

We have been conditioned by roughly 500 years of “freedom of expression” since the Renaissance to expect artists’ personal feelings to play a major role in their creative work. In fact, we have a separate designation for pictorial images that fail to communicate on the “expressive” level: we call them “illustration.” Society’s lesser esteem for illustrations may be gauged by the fact that we rarely find them in museums next to “Fine Art.” (An exception may be N.C. Wyeth and his followers in the “Brandywine tradition.”)

Some artists, observing this, have supposed that the “real” substance of costly art in museums is in its expressiveness, and thus have almost totally subjugated the descriptive aspect of their work. More recently, a rebellion on the part of “photo-realists” has swung the pendulum back to almost pure description — a style which virtually negates any expressive intervention on the part of the artist.

Under these conditions, it is critical that we become sensitive to the pervasive tension between expressive and descriptive aspects of various art forms.

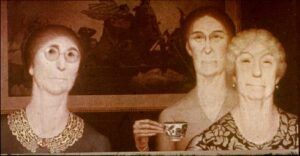

Perhaps comparison of two works dealing with somewhat similar subject-matter might prove helpful in this regard. In Fig. 1-8, we have a painting by Willem DeKooning entitled Woman I (1950), and in Fig. 1-9, we see Grant Wood’s Daughters of the American Revolution. Each is descriptive of singularly formidable women, stimulating universal emotions generated by strong-willed maternal images. What is important here is not to decide which is the “better” art work, but to distinguish between kinds of experience which we may derive from one approach or the other.

Fig. 1-9. Grant Wood’s Daughters of the American Revolution describes without much editorial comment.

Grant Wood presents us with a symbol of traditional mid-American conservatism, social stratification and toughness-of-character, all reinforced by a well-known image of patriotism, Leutze’s painting of Washington Crossing the Delaware. Wood’s means of communication are highly “illustrative,” relying on extensive description of costume and jewelry, a tea cup and the somewhat stereotypical features of this group of mid-Western ladies. Whether these are “good folks” or not is left very much to personal choice — based perhaps on one’s prior experience with lantern-jawed socialites from small-town U.S.A. Wood communicates information essential for any viewer to arrive at a personal response to the painting, but does not pre-judge the feelings aroused.

DeKooning on the other hand lets us know right away that he has deep feelings of anxiety and hostility toward women of the type he depicts. He doesn’t need to elaborate the image with particulars of costume, locale, age or social status in order to reinforce that message. The expressive elements in his portrayal are a gray or “neutral” color scheme punctuated with “angry” slashes of crimson and heavy black line. The figure is distorted by enlarged breasts and wide staring eyes, with big, manipulative hands capable of reminding one of a ferocious nanny or school teacher of bygone days. DeKooning leaves us no choice here. This is a symbol of aggression about which we may know very little, but about which we must feel excruciating discomfort.

Fig. 1-1 1. (right) Mary Cassatt reveals a great deal about social status of young women depicted in A Cup of Tea (1880).

Confronting these contrasting images, each of us must discover his or her own threshold of taste for cool, descriptive language on one hand, and for expressive distortion on the other. Our taste in this matter will probably depend in large measure on how we have been conditioned by past experience, and on where we encounter the images. (We can usually accept the boldly expressive in an “impersonal” art gallery more readily than in our home.) Any painted or sculptured image can vary all the way “from Wood to DeKooning” and there will be those whose taste and experience will correspond.

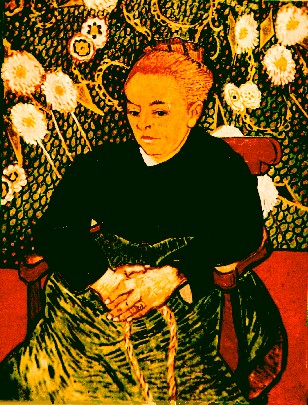

Another useful contrast is Mary Cassatt’s painting, A Cup of Tea, 1880 (Fig. 1-11) and Vincent Van Gogh’s roughly contemporary study of his landlady, La Berceuse, 1889 (Fig. 1-10). Cassatt is very detached in her painstaking still-life of the tea-service (she had been a Philadelphia socialite before going to Paris), while Van Gogh flattens his subject and sets her against bold and distracting wallpaper designs which “load’ the image with subjective connotations of tension. As with DeKooning’s Woman I, Van Gogh’s image is more concerned with feelings than with descriptive detail. Cassatt’s two young ladies, on the other hand, reveal alot about their social status and economic condition, as did Wood’s matrons. Cassatt remains closer to a 19th-century tradition which saw painting as a genteel form of “communication,” while Van Gogh looks ahead to the Expressionism of the 20th century.

Not all artists have such clearly differentiated styles as Wood and DeKooning, or Cassatt and Van Gogh. Some combine a measure of both objective and subjective characteristics in images that convey strong feelings without radical departure from descriptive norms.

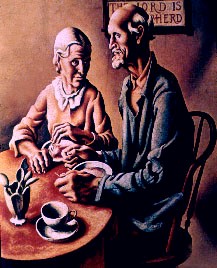

Such an artist was Thomas Hart Benton (Fig. 1-12), an American contemporary of Grant Wood, who described nature with a measure of visual objectivity, while at the same time expressing strong opinions about social issues. Benton, who was politician as well as artist, directed his art more at the “American public” than elite arbiters of American taste, and thus his expressiveness seldom was at the expense of natural appearances.

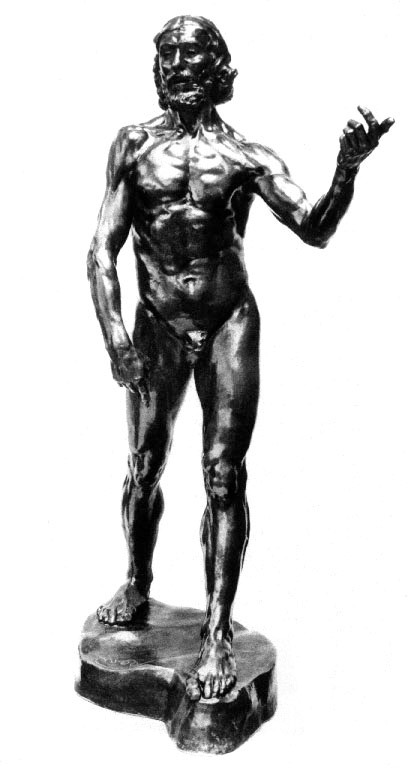

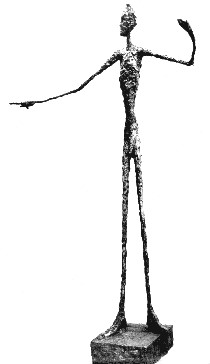

This “polarity” of emotion and objectivity is no less a factor in sculpture than in painting. A work entitled John the Baptist (1890) by Rodin (Fig. 1-13) is highly anatomical or “true to life,” while the drastically elongated Figure of a Man by Alberto Giacometti, (Fig. 1-14) has emotional impact similar to DeKooning’s explosive Woman I.

Giacometti sacrifices descriptiveness on behalf of deeper emotional intentions, clearly distorting optical reality to create a sense of aesceticism in this haunting figure. His viewpoint was impacted by disillusionments of economic collapse and National Socialism in the 1930’s and 40’s, while Rodin lived in an era of bourgeoise optimism.

Ironically, 19th century critics scolded Rodin for “copying nature,” while but a couple of generations later, post-WWII critics found Giacometti too radical in his refutation of Classical norms of proportion and anatomical description.

Prior to Rodin, during the Victorian Age, description was typically wrapped in (more-or-less) idealism. After two World conflicts and the Cubist revolt, however, critical taste in Giacometti’s time demanded more expression than anatomical accuracy. Seen in this historical perspective, Giacometti appears no more radical for his era than Rodin’s “realism” had been in the eyes of Parisian critics of the 1890s.

.

Fig. 1-10. Vincent Van Gogh describes his landlady in a tense, expressive mood in La Berceuse (below, 1889).

Fig. 1-12. Thomas Hart Benton achieves a fusion of expression and description in The Lord is My Shepherd (1926).

Figs. 1-13 & 1-14 contrast Rodin’s John the Baptist Preaching (1890/ above) and Giacometti’s Figure of a Man (1947/ below), signifying the 20th century’s evolution toward expression.