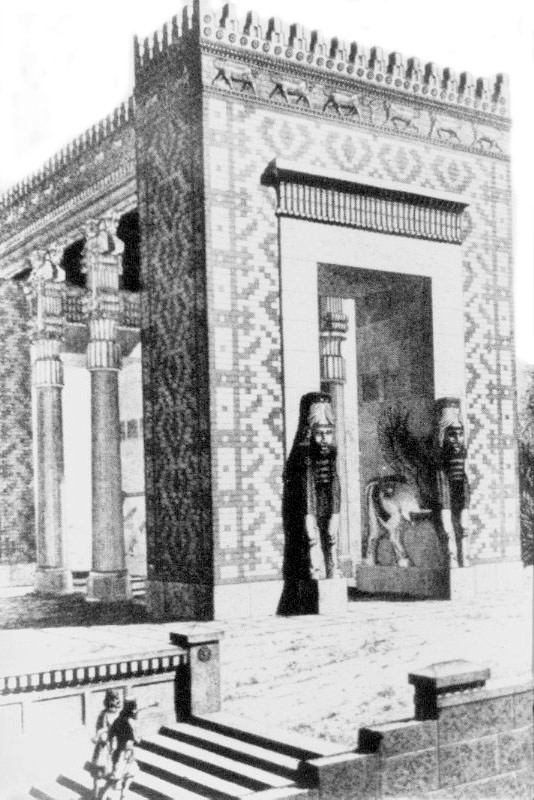

Throughout most of recorded history, there has not been the confusion about “good/bad” art which characterizes our time. For one thing, the majority of early monumental works in Egypt, Mesopotamia or Greece were not made for the “av- erage citizen.” The “man in the street” accepted tastes of political or religious “power brokers” who established the culture’s “norms” of taste. (Fig. 1)

It is also significant that craftsmen who carved these symbols for society (or later cast them in bronze) were seldom artistic “prophets” such as Leonardo or Van Gogh, but merely “artisans” who created images for the ruling class. Under these circumstances, there was little room for argument about new forms of artistic expression. Artists produced symbols of group consciousness rather than articles of “self-expression.”

With the Renaissance, the role of artists changed abruptly, and since that time (about 1400 AD), there has rarely been widespread agreement as to what the artist’s function is in society. Artists could no longer look to the absolute authority of a pharaoh, king or pope to define subject matter or style. For a time, wealthy patrons such as the Medici Family “created taste.” But with the “democratization” of modern industrial society, these critical choices are often made in the marketplace, and are subject to unpredictable swings of popular taste.

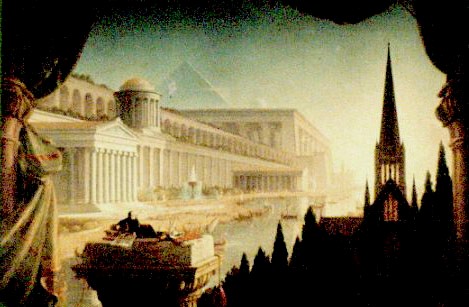

The most loyal patron of 19th-century American artist, Thomas Cole, for example, was a vegetable-merchant in New York City, who had quite different ideas about what Cole should be painting than did the artist himself. Cole was torn between the demands of economic survival (represented by his patron’s taste for “unspoiled landscapes” such as Fig. 1-2) and a Romantic notion (with European roots) of unfettered “imagination,” to which the painter himself subscribed (Fig. 1-3).

Small wonder there is an occasional gulf between artists and a public which has only vague clues as to what motivates a painter or sculptor.

Though arbiters of taste in Western society are no longer high priests or kings, museum curators, collectors and investors often appear to establish market value by whim or manipulation of tastes. Under these circumstances, perhaps the task of an aspiring “insider” is to establish some canon of value that can function successfully both within and outside the marketplace. In that way, we will be able to confront works — whether exotic or pedestrian, conventionally attractive or radically unorthodox, technically adept or spontaneous and crude, new or old — with some measure of assurance that we are not being duped by “trendy” merchants. Developing this “canon of value” is what the balance of this book purports to be about.

Is it Art?

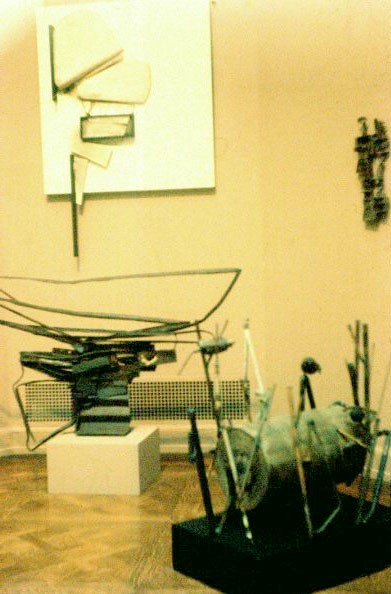

Possibly one of the more unsettling experiences many of us have had is to be confronted by works in a gallery or museum that don’t reveal any of the qualities we have come to expect in historically celebrated art works. By their presence there, these objects gain a certain cultural status which seems alien to our expectations. (Fig. 1-4)

If they derive from some other time and place, we can sometimes shrug them off as “strange,” but if they represent the culture in which we live, we are understandably troubled by them, or occasionally angered!

Some earlier societies have not distinguished between “Fine Art” and other less-prestigious art forms (also called “popular” or “vernacular” arts). When art becomes isolated from society in a museum setting or by having great monetary value, it takes on a special burden of social significance. Such art forms appear to have endorsement of cultural institutions of the age, though in many instances that may not be entirely true.

With this confusion about what “represents our culture,” however, it is important for us to have at least minimal criteria with which to evaluate works that purport to speak for our time — remembering, however, that when artists experience ugliness and frustration, we cannot hold them hostage to some apriori standard of “beauty” as one of those criteria.

Some Possible Criteria

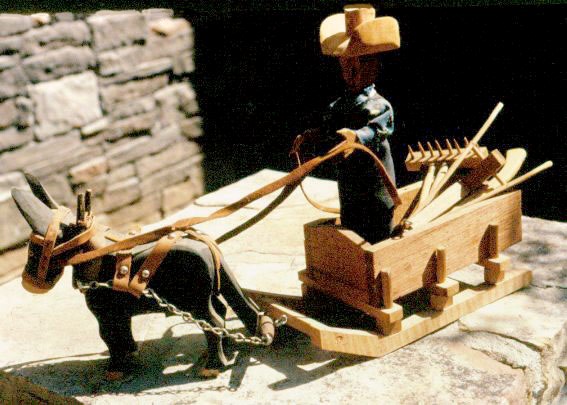

One means of discovering such criteria is to consider a contemporary work illustrated in Fig. 1-5, commonly described as “Folk Art,” the work of an artist with no academic training. Folk Art increasingly appears in our museums and galleries, even though it is an expression of “popular culture” in much the way Jazz is. If this object has some properties we associate with “Fine Art,” let’s see what constellation of values enables us to compare it with more sophisticated works traditionally found in art galleries.

Certainly it is unique, an original conception (even though the artist, Willard Watson, does reproduce the piece himself). Each is one-of-a- kind, and can’t be found in exact duplicate at some neighborhood department store. Apparently scarcity or exclusiveness have something to do with what we consider “art.” That is why a reproduction of a Rembrandt painting bears no “economic” relationship to the original. Paintings sold out of trailer-trucks or motels are a “commodity” manufactured assembly-line fashion to meet decorator specifications of color and subject-matter, and thus lack the integrity of individuation required for “significant” art.

Secondly, this piece is imaginative, using familiar materials such as wood, leather and cloth in unfamiliar ways. One suspects at first that it might be a child’s toy, but on more careful scrutiny it appears too complex in its handling of detail to be “merely a toy.” It seems to be “saying something” about rural life.

Art can have “meaning” on any number of levels — but without significant association for mind or senses, a work quickly loses one’s interest.

A third characteristic which this piece manifests is expressiveness. The image it conveys of an old farmer has possible meaning on a nostalgic level, conveying a variety of associations, such as “grandparents working the land,” for instance. It also may have some pleasurable connections with our childhood memories of “pull-toys.”

These three attributes then –uniqueness, imagination and expressiveness — appear close to the heart of almost any “significant” creative activity in the visual arts, as well as in poetry, music, drama and dance, to name a few.

But is there more? Indeed, it is hard to visualize a work of importance in the field of art which fails utterly to reveal some element of skill or craftsmanship on the part of its producer. Who can envision a profoundly moving work that totally lacks control of its medium – be it color, movement, language or even sound produced with a synthesizer?

The artist is a manipulator of some substance through which he or she communicates feelings. Without adequate control of that medium, transmission of sensory or mental impressions is blunted. The Folk Art piece with which we initiated the question, “Is it Art?” certainly puts materials together masterfully, and thus it appears to fall into the category of significant artistic statement.

When we confront an unfamiliar work which apparently has qualities associated with art, applying these simple criteria may enable us to arrive at a reasonable first assessment. We might then want to pursue further background on the piece before concluding it has no artistic meaning for us. At that point, however, we should no longer feel baffled or confused because the object appears in a place that implies it has great cultural value.

Incidentally, an interesting sidelight on Willard Watson’s piece is the minimal care he has given to carving facial features of the figure (Fig.1-7). Other details such as hands, arms that swivel up and down, reins and carefully-fitted clothing are quite eloquent, and the hat is a marvelous example of three-dimensional form. But the face is flat and uninteresting. In the manner of “primitive” works of many cultures, personality or individuality are not significant here. The work is more of a symbol or icon than a portrait.