Sculpture: Add or Subtract

Carved wooden figure, Reclining Nude by American, Ellen Key Oberg (Fig. 8-1, Mahogany), exemplifies subtractive process by preserving integrity of original block.

In Chapters 1 through 7, we have looked at various sculptural images, and in doing so, developed a working vocabulary which enables us to distinguish forms that are objective and non-objective, open and closed, tactile or visual, conceptual or perceptual, literary, plastic and decorative, biomorphic, intellectual and/or space-shy. We have also noted that ponderation is a critical factor in both sculpture and architecture, as is the tension between mass and surface-embellishment.

Sensitivity to these variables can substantially enhance one’s experience of sculpture and help transcend ethnic, cultural and historical boundaries that sometimes make a trip to the Museum somewhat baffling.

If there is any over-arching aspect effecting sculptural characteristics such as those cited above, it would seem to be the artist’s choice of sculptural process. Carved (or glyptic) sculpture typically starts from a block of stone or wood — which lends indelible traits to the finished statement: grain, shape, texture, hardness, color, idiosyncracy, static properties, etc. The artist’s role in relation to the block is purely subtractive, removing material from the original matrix to “realize” that residual shape visualized at the outset.

Additive form, on the other hand, may be “extended” by accretion of such substances as clay, plastilene, plaster, polyesters, metal and a variety of other modern technologies.

Carved wood form by Barbara Hepworth (Fig. 8-4, Pelaqos) bears indelible unity derived from original block. “Additive” visual element of wires-within creates decorative aspect as well as lyrical reference to stringed instrument.

When an artist elects to use additive process to fabricate a threedimensional image, outcomes depend heavily on a series of choices influenced by the medium. There is ample opportunity for improvization here, because the artist is not limited by an initial, geometric form (or conception).

With freedom, however, comes a challange: for the artist must endow the additive form with limits acceptable to the eye of the beholder. That may not sound like a tremendous feat, but in the balance of Chapter 8 we will consider possible outcomes.

A “mixed” technique involving both additive and subtractive phases is also characteristic of the production of Terra-Cotta sculpture (fired clay) and such processes as “ lost-wax bronze casting,” the technique refined by Etruscan and Greek craftsmen.

“Lost Wax” Process

In the casting process, one builds an initial “model” of clay, plastilene (a waxy clay), styro-foam or plaster (the additive phase), which is then “refined“ (subtractive phase). Before a mold is made of the exterior surface, a sometimes-elaborate system of vents for bronze or hot gas is installed, and the whole is surrounded with a refractory shell. Emptied, the shell is reassembled, its interior coated with a thin layer of hot wax and when cool, the interior is filled with a refractory mix called ludo (plaster and volcanic ash) held in place by pins which penetrate the wax layer. The whole is placed in a “burn-out kiln,” which evacuates the wax layer and sprues, later to be replaced by molten metal in the “final pour.”

If one compares the Picasso Cock (Fig. 8-2) with Madonna by Henry Rox (Fig. 8-3), one can easily see that Picasso might well have created more appendages (stressing feathers, wings, spurs, etc.), with no technical impediment. But surely the design would have suffered a loss of coherence. It is an open form, with considerable attention to separate “parts” (conceptual) and to a rough (stucco-like) surface treatment. There is also a suggestion that the artist conceived his subject almost as “high relief” rather than “in the round.”

Additive process conditions linear style of Giacometti’s Snooping 192 Animals (Fig. 8-5, plaster on metal, left), just as subtractive approach defines Richard O’Hanlon’s cohesive stone-carving , Por cupine (right, Fig. 8-6).

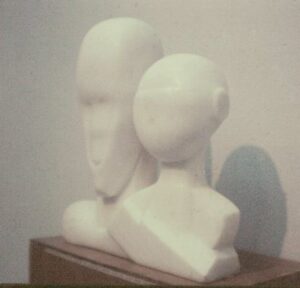

The Rox Terra-Cotta, on the other hand, appears to have no projections such as hands, arms or other extensions of the central mass of clay (perceptual) — for appendages are inherently unstable both in the unfired and fired states, and might arguably detract from the “wholeness” of the Mother/Child union. The figures are “built” as a self-supporting unit which is hollow, and the artist can only advance as the lower portions dry enough to become structural. One would assume this piece is conceived to be observed from the back as well as from a frontal point-of-view.

In contrast to the complex additive and “mixed” production processes, it would seem that wood-carvers avoid technical complexity by “going directly” to their intended image in the carved block. Recent developments in wood technology have permitted artists to impregnate large blocks of material with chemical substances which virtually eliminate risks of checking and splitting. But, like manufacturers of fine musical instruments and furniture, sculptors often have to age (or soak) their wood for months or years before commencing the carving process. Even blocks of stone change markedly with exposure to air for a significant period.

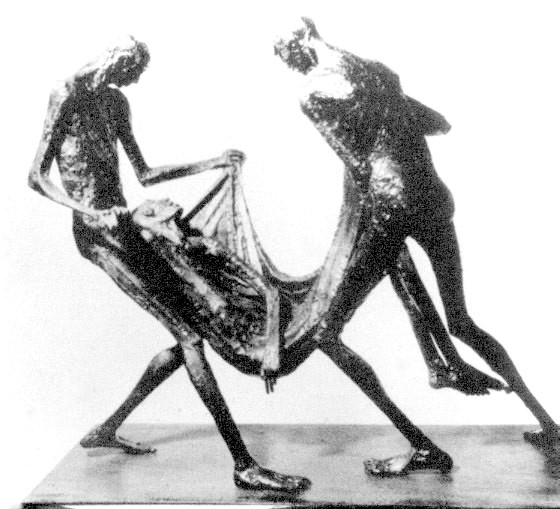

Two Bronze images of children have radically different characteristics via the additive process: Vigeland’s Unborn Child (Fig. 8-10, left) from Oslo park is an icon with perceptual power, while Lehmbruck’s Crawling Child (Fig. 8-11, right, 1907) is eloquently theatrical and fosters conceptual interest in mood and body parts.

The original mass of a tree delimits Barbara Hepworth’s form (Fig. 8-4), and indeed it is the “discipline” of designing within that matrix that gives power to her conception. By suggesting a spherical form evolving toward a helix, and coating the “interior” white to contrast exterior woodgrain, the artist evokes a sense of organicism reminiscent of a half-peeled apple.

It is possible to discern marked differences evoked by a subtractive as opposed to an additive methodology by comparing Snooping Animals by Giacometti (Fig. 8-5, plaster and horsehair on metal armature) with a stone-carving (Fig. 8-6, Porcupine) by American artist, Richard O’Hanlon. Giacometti’s plaster-over-metal dog and cat forms are linear, attenuated, flat, kinetic, conceptual and visually interesting, while O’Hanlon’s porcupine is massive, tactile, static and perceptual. The Porcupine image coheres within tight constraints of a boulder-form in which it had its genesis.

Early Ghiberti bronze panel (Fig. 8-13, left) evidences strong planar structure in shallow space, along with static figures. A generation later, Gates of Paradise (Fig. 8-14, right) utilizes nuances of wax medium to explore “aerial perspective” in panel from gilded Story of Joshua, Florence Baptistry.

Further evidence of the weight of process in determining character of a sculptor’s work may be found in comparison of two pieces by Jacques Lipchitz: the earliest, a carving (Fig. 8-7, stone, 1919) and a later work (Fig. 8-8, bronze, 1943), the result of an additive process.

Obviously influenced by prevailing Cubist aesthetic sensibility, the artist’s earlier carving has planar frontality of a canvas by Picasso. Mindful of plastic issues of coherence, Lipchitz “connects” parallel diagonals and radial arcs in a complex pattern of interlocking shapes. Then, stimulated by Expressionist works emergent during World War II, we see Lipchitz becoming more visual -almost “painterly” — by 1943. His bronze Prayer, a figurative piece probably modeled in Plastilene over metal armature, contains myriad fanciful, natural forms unified more by literary spirit than by mass, geometry or plastic rhythms. Clearly, the “freedom” of an additive process has inspired a highly decorative, “fairy-tale” treatment of otherwise somber material.

The difficulty of orchestrating any such complex of interrelated forms with an additive medium is perhaps nowhere more eloquently evidenced than in the tour de force of Rodin: The Gates of Hell (Fig. 8-9) which consumed the artist at the end of his career. Seen here in a detail (surmounted by the principal surviving masterpiece from its chaotic transom — the famous Thinker), Rodin’s struggle to establish “boundaries” to his plastic organization is everywhere evident. Like Hieronymus Bosch’s early 16th-century painted treatises on man’s fallibility, the Gates succumb to a seductive virtue of Rodin’s medium — the artist has no limit to what he can pour into the murky brew.

The Renaissance Master, Donatello, evolves from early carving (Fig. 8-16, top, Marble Assumption, 1427) to more elaborate, gilded Sandstone relief (Fig. 8-17, middle, Annunciation, 1438-40), and culminates with highly pictorial, Bronze Deposition (Fig. 8-18, bottom, 1460-66).

Thus, you might legitimately ask: Is it the innate “reductive” influence of the “block” of stone or wood that “saves” subtractive sculpture from “temptations” of additive technique? Indeed, it would seem to this writer that the artist’s choiceof-sculptural-medium is not the decisive factor here. We have for evidence, countless works in Bronze (additive genesis) which manifest profound “consciousness-of-the-whole.”

The most critical factor in determining levels of plastic coherence appears to be the artist’s penchant for Apollonian order (Fig. 8-10) or for Dionysian less of the medium. Lehmbruck’s expressive power (Fig. 8-11), regard Crawling Child- E~XPRESSIVE ~utilizes open and mobile naturalism for psycho- POWER emotional energy, while Vigeland’s Unborn Child makes the wholistic leap to symbolic status with closed, geometric form which might well have been carved from a wood or stone block.

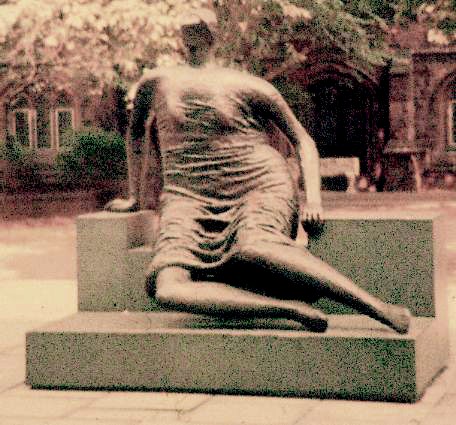

It was noted in our Prologue that Donatello gravitated toward expressive wood-carving (Figs. 6 & 6a) and bronze “murals” in his late period. As with Michelangelo, Rodin, Henry Moore (Fig. 8-12),Vigeland and other lifetime practitioners, the “mature” trend seems to be toward more Dionysian spontaneity and expressiveness, once Apollonian rigors have been authoritatively addressed.

This is surely the case with Ghiberti, the great Early Renaissance sculptor who won the competition for doors of the Florence Baptistry in 1402. His winning design was more “classical” than his leading competitor, Brunelleschi (who “looked back” to more Gothic spatial consciousness). The winning doors required almost 23 years to complete (Fig. 8-13 is a detail), and one can experience Ghiberti’s solid pyramidal massing of figures in a controlled stagelike space. When commissioned to invest another quarter-century in a second set of doors, it is somewhat ironic that Ghiberti seized upon a system of single-point perspective for which Brunelleschi is generally credited, to create elaborate bronze “spatial symphonies” ( as in Fig. 8-14, The Story of Joshua). The artist’s earlier carved St. Matthew (Fig. 8-15, stone), though less Tuscan than Donatello’s Lo Zuccone (Fig. 5a), nevertheless embodied sturdy “Latinisms” of Italian Gothic Style without visual refinements of the later additive bronze relief panels.

Donatello’s aesthetic odyessy traversed a broad spectrum from early Tuscan emphasis on mass and tactile values (principally carved, as in Fig. 8-16), to his mid-period influenced by “Classical” Latin focus on drapery and elaborate surfaces, encountered while in Rome with Brunelleschi (Fig. 8-17, also carved). Then, in the 1460’s, Donatello chose wax-for-bronze to execute a visually-complex Pulpit panel for San Lorenzo, in which layers of figures are spatially jumbled and light (surface effects) ultimately triumphs over form (Fig. 8-18, Bronze).

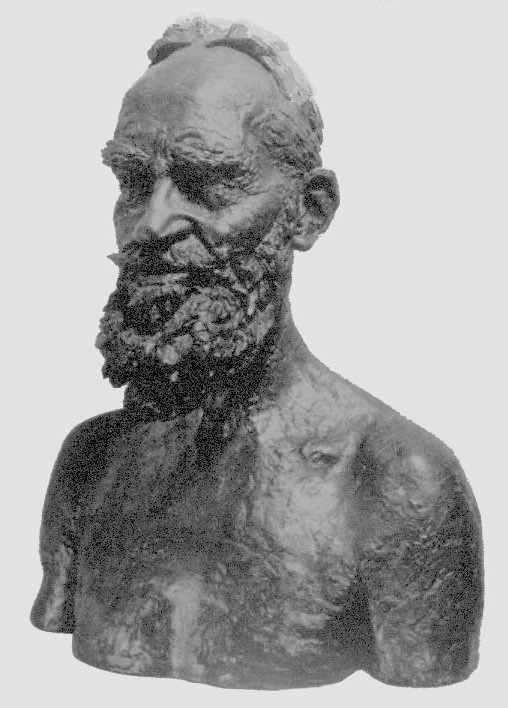

Universal tactile language predominates in Zorach’s sculpturesque, Head of Christ (Fig. 8-22, left), while eloquent specificity characterizes pictorial portrait of Cardinal Glennon by Schnittmann (Fig. 8-23, right).

These typical evolutionary stages, seen here in a particular historical context, are common enough that we have developed terminology for certain works of subtractive or additive origin. Carved (subtractive) sculpture with an emphasis on massive, tactile forms (geometry), expression of the “glyptic” material (e.g. stone, wood), and often with rustic surface treatment, has been described as Sculpturesque. In contrast to this type of sculptural expression, there is Pictorial style — based largely on additive technique (descriptive nuances attainable with wax, clay or plaster) and inclining toward optical verisimilitude (“likeness”) and “psychology” rather than to formal values of solid geometry, relationship of masses, contrasting negative space and ponderation.

One may have strong personal tastes in this area, but the history of sculpture would indicate that value judgments must be suspended if one is attempting to determine what “real” sculpture is at its best — for masterpieces abound in both genres, and often (as with Donatello), from the hand of the same master.

The British-American sculptor, Jacob Epstein, subtractive process in a work called Mother and Child carved from Marble (Fig. 8-19, 1913). Later, he chose Bronze as his primary medium (see his Portrait of Oriol Ross, Chap. 2, Fig. 2-3), and executed an additive Madonna and Child (Fig. 8-20) which is highly pictorial. One can easily discern that for Epstein, deep penetration of psychological fabric outweighs the “right arrangement of masses,”and thus, he found his metier in the pictorial rather than in the sculpturesque. (See portrait of George Bernard Shaw, Fig. 8-21).

Carved work by Glicenstein ( The Player , Fig. 8-26, left, Mahogany) combines veiled emotion and geometry while Pictorial Scrubwoman by Mahonri Young (Fig. 8-27, right, bronze) blunts typical psychological immediacy of works done by additive method.

To contrast Sculpturesque and Pictorial style, we might compare Zorach’s carved Stone Head of Christ (Fig. 8-22 and also Fig. 6-40) with a remarkable additive portrait from the Cardinal Glennon Memorial by S. S. Schnittmann (Fig. 8-23). Like Epstein’s G. B. Shaw, the Glennon image (which has the patina of textured clay) displays uniquely idiosyncratic facets of the Cardinal’s persona, relying heavily on abrupt changes in light and shadow to animate the ruggedly-pensive face. Searching for a universal Christ-image created quite a differ-ent challange for Zorach, however, and we see him resorting to somewhat conventional features and tactile rather than visual stimuli expressed as both textured and polished Stone.

One sees a clear time in comparing the Zorach and divergence of intention relative to time in comparing the Zorach and Schnittmann portraits (Figs. 8-22 & 8-23) and also the O’Hanlon and Haver bird images (Figs. 8-24 & 8-25) overpage: The carvers, Zorach and O’Hanlon, seem to seek a “timeless” outcome akin to 4th-Dynasty Egyptians’, while practicioners of the additive school generally celebrate the moment. Stone as a medium appears to engender that quest for the “eternal” more consistently than sculpture carved from wood.

Compact energy-in-expression expands our perception of scale in Prancing Foal (Fig. 8-30, left, bronze) by Renee Sintenis and Flight by Fritz Koening (Fig. 8-31, right, bronze). Both are from 20th-cen.

Wood-carvers of a “Northern” perspective offer an especially piquant contrast to the more “Mediterranean” taste for static and durable stonecarvings. Barlach’s Man Alone (Fig. 7-31) and Man in Stocks (Fig. 6-35) — both carved in wood — embody movement and pathos which inevitably stimulate a “sense of the moment.”

A contemporary American wood-carving by Glicenstein (The Player, Fig. 8-26), with its embodiment of transient mood and empathetic body-language paradoxically hovers between the “timeless and the momentary.” We can also see that a Pictorial approach does not always satisfy our human affinity for immediacy, since despite having temporal properties of a “snap-shot,” Scrubwoman by Mahonri Young (Fig. 8-27, Bronze) fails to engage us on the same level of psychological poignancy as do the Barlachs cited above.

Another word we use to describe sculpture with formal power beyond its actual physical size is the term, “Monumental.” It acknowledges that physically-small works seen in illustration can appear “larger than life,” due to compact arrangement of their tactile geometry, and absence of descriptive detail that makes “scale” apparent.

Direct engagement of the artist with each phase of production is one virtue of Terra Cotta, A wakening (Fig. 8-34 with detail) by Maria Martins, 1960.

Such works are Monkey by John Flannagan (Fig. 8-28, stone, 1939) and Aaron Goodelman’s Happy Landing (Fig. 8-29/stone), which also utilize unresolved tension to create images endowed with uncommon energy.

Kinetic forms, sculpture with implied (or in the case of an Alexander Calder “Mobile,” actual) mobility can also influence one’s sense of the monumentality of a piece. Two relevant examples from the 20th cen. are of a piece. Two relevant examples Prancing Foal by Renee Sintenis (Fig. 8-30) and Flight by Fritz Koening (Fig. 8-31), both in bronze. Sculptors such as Lachaise, Nadelman and Milles have expanded frontiers of kinetic language by exploit-ing movement and tensile strength of apparently “weightless” forms cast in bronze.

TERRA COTTA — AN ANCIENT PATH

One cannot properly conclude this discussion of additive/subtractive, sculpturesque/pictorial, static/kinetic modalities for production of threedimensional form without a further acknowledgment of the unique synthesis represented by the ancient art of Terra Cotta sculpture.

Among 20th-century masters of this method is the American artist, Betty Davenport Ford of California, whose Reclining Gazelle and Puma are pictured in Figs. 8-32 and 8-33, respectively. Like the graphic artist who executes drawings and color studies prior to a painted image, Ford makes many clay sketches preparatory to initiating a “full-sized” piece. Structural issues are resolved and clay mixed to produce appropriate color, sufficient “plasticity” to hold the unfired work together, and refractory (heat-resistant) materials which will withstand in excess of 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit during the firing phase of the process.

Sacrificing optical “truth” for spiritual reality, Charles Umlauf chooses Terra Cotta for distortions of his Pieta (Fig. 8-35)

The work is “built-up” completely hollow, with “arches” sprung like a Gothic cathedral by forming tube-like appendages into torso, neck or tail. Analagous to a poured concrete structure in which each “lift” must set before the next can be added, the clay hardens to a “leather-hard” state before work above can continue. Air-drying must be meticulously controlled to prevent cracks from developing as refinements are made in the final “subtractive” phase of the process.

Less cerebral/ mechanical than the “lost-wax” technique of bronzecasting, Terra Cotta is highly intuitive, and offers the artist options ranging from the Sculpturesque to the Pictorial without intervention of specialized artisans often required in stonecarving, pouring bronze, chasing cast surfaces or welding complex forms.

As the Greeks concluded centuries ago, Bronze or stone are the materials of choice for “public” monuments exposed to the elements. For more personal expression in home or office, however, Terra Cotta has a warmth and range of emotion which is incomparable. (See Fig. 8-34, Awakening, and detail, by Maria Martins)

Expressionism is primarily thought of as a style of painting popular after the paroxysm of WW II, but in Pieta (Fig. 8-35) here translated into Terra Cotta by Charles Umlauf, the aberrant forms take on meaning laden with overtones of Nazi concentration camps. Clay has this deeply subjective dimension, as we can see in a piece simply called Mask (Fig. 8-36, Terra Cotta) by Giacomo Manzu, which captures as poignant an impression of life as the Umlauf lament does of death. Such expression goes beyond description to enter the realm of visual poetry.

Mask by Giacomo Manzu reveals subjective potential of clay (Fig. 8-36) in delicate transcription of a woman’s emotional state.

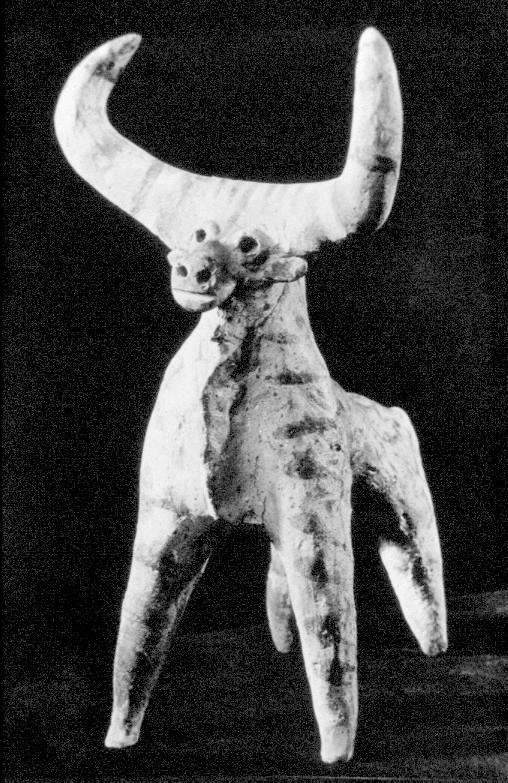

The powerful potential of this humble medium — which has been most critical for a Folk Art tradition stretching back into Egypt, Africa, China and much of Europe — is notably evident in an animated Persian icon of a Bull (Fig. 8-37) from roughly 1,000 B.C., which displays as much sentience with body-language and nuance of expression as does the Manzu Mask of 3,000 years later.

Indeed, if Homo sapiens has been the “toolmaker,”clay would seem to have remained the nearly-exclusive province of human fingers — untrammeled by chisel, hammer, welding torch or chain-saw.

BUILT-UP OR CONSTRUCTIVIST SCULPTURE

Clearly, ingenuity of the “tool-maker” has made an imprint on the evolution of three-dimensional imagery, and it would be a serious omission to ignore the considerable achievements in an area we call “Built-up” or “Constructivist” Sculpture. It is in this domain, in particular, that we find modern technology has triumphed in the ages-long struggle with “ponderation”– the perceptual experience of earth’s gravitational demands on Homo sapiens.

At first, metalurgy gave sculptor and architect the language with which to confound gravity. And since then, such technologies as plastic resins, polyesters and other man-made materials have given designers means to loose the bonds of Icarus.

Leo Steppat’s Rearing Stallion (Fig. 8-38 and detail) uses welded steel to create upward thrust impossible with stone or Terra Cotta.

Take for example a Rearing Stallion by Leo Steppat (Fig. 8-38 and detail) which is fabricated with forged iron. A massive work, it is built with metal plate — using an acetylene torch to cut the sheet iron before it is welded together. Cantilevered in space in defiance of gravity, Steppat’s virtuosic celebration of the instant in many ways rebuffs the stonecutter’s perennial quest for eternity.

Gravity seems to be “center-stage” in many pieces of Constructivist sculpture, such as Suspended (Fig. 8-39) by Menashe Kadishman, or David Smith’s Cock Fight (Fig. 8-40), both welded steel. But in the vast scheme of artistic expression, one can’t help but wonder if history will be as celebratory about paeans to gravitational freedom as to, say, Renaissance Humanism or Gothic piety.

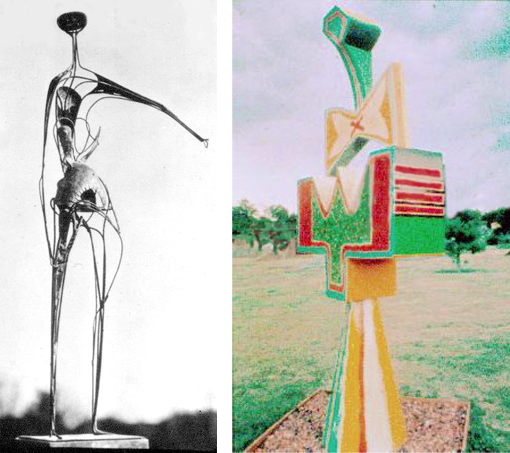

Somewhat more hospitable to traditional Western cultural tradition are figurative sculptures in the Constructivist Style, such as Reg Butler’s Woman Standing, made of Bronze, wire and Sheet Metal (Fig. 8-41) and a polychromed piece entitled Holy Man I by Ida Kohlmeyer (Fig. 8-42). Though not especially optimistic about the development of Modern man, these works continue the dialogue regarding post-Renaissance civilization.

Giacometti’s The Palace at 4 A.M. (Fig. 8-45, 1932-38, left) articulates space and domestic story-line, while Lassaw’s Moons of Saturn (Fig. 8-46, 1954, right) evokes Minimalist Universe.

Historically, when sculpture has been pressed into a narrative role in monolithic cultures such as Egyptian, Greek, or Medieval Christian, it has been as an architectural frieze. In more recent times, however, the French artist, Rodin ventured a story-telling work in bronze — his famous Burghers of Calais (Fig. 8-43, 1886-87), which Rodin meticulously “developed anatomically” in Plastilene before “clothing” them with “Flemish robes.”

For a contemporary studio artist to venture into this realm of narrative sculpture with only sheets of steel and a welding torch clearly requires real hutzpah. Notable in this regard is the work of Barbara Lekberg, exemplified by her welded-steel version of the Deposition (Fig. 8-44) seen above. Lekberg conjures with theatricality here, but her visible welding process provides sufficient psychic distance for the work to succeed.

Lyricism in steel and plastic may define both the Brussels Construction of Jose de Rivera (Fig. 8-47, 1958/Stainless, left) and Naum Gabo’s Linear Construction, (Fig. 8-48, Plastic, right), sculptures exploiting line, light and movement, elements of graphic as well as haptic communication.

Where Constructivist Sculpture will lead us in the 21st Century is hard to predict in the opening decade, but it appears that the revolution in castables, vacuum injected molds, lightweight metals such as titanium, and a host of new resins now bonded with little more than paper to build airplanes, should easily render the time-honored processes of carving and bronze-casting obsolescent. One can predict, however, that as the pendulum swings inexorably toward higher levels of technology, we will also see a concomitant rise in the production of naive or Folk Art — as in the past — relying on simple materials such as fired clay and assemblages of wood or metal to express ideals of a less-urbane culture.

Inevitably, it seems the reductive process -whether graphic or three-dimensional — trends toward the linear as a baseline of rudimentary human “sign-making.” Divested of its tactile or planar aspect, Constructivist language appears to gravitate toward either Literary content or “pure aesthetic” expression. Illustrated works by Alberto Giacometti (Fig. 8-45) and Ibram Lassaw (Fig. 8-46) are somewhat akin to “program music,” while the more kinetic statements in Figs. 8-47 and 8-48 by Jose de Rivera and Naum Gabo express fundamental delight in aesthetic possibilities of the tensile materials, stainless steel and plastic.

Sculpture by Picasso (Fig. 8-2, Cock, Bronze/ 1932) reflects additive process, probably plaster over metal armature. Tensile strength of metal allows un-restricted projection of tail feathers and wings into space.

Demands of Terra-Cotta technique require artist to maintain integrity of nonstructural (clay) form during plastic (wet) phase of construction. Hence its compactness. Fig. 8-3 is Madonna by American artist, Henry Rox.

Jacques Lipchitz exhibits radical alteration of style between 1919 carving (Fig. 8-7, left) and additive Pierrot with Clarinet, Prayer in Bronze (Fig. 8-8, 1943, right) revealing power of medium and process.

Rodin’s effort to inform his Gates of Hell (Fig. 8-9, Bronze 1917) with plastic coherence suggests complexity of design in an additive medium.

“Late” Henry Moore figure at Yale Univ. (Fig. 8-12 , Draped Seated Woman ‘57-’58, bronze) reveals “instability” and heavily “etched” surface of his postWWII response to “underground” bombings.

Ghiberti’s St. Matthew (Fig. 8-15, stone) eschews complex visual effects of his later additive productions. The carving process discourages spatial complexity and elaborate surface treatment permitted by a built-up medium.

From early carved work reflecting Cubist values (Fig. 8-19, Mother and Child, top), Jacob Epstein evolved to pictorial (additive) Madonna and Child (Fig. 8-20, Bronze ).

Portrait of George Bernard Shaw (Fig. 8-21, Bronze ) developed “painterly” surface effects to another level.

A Pictorial approach to Project California Condor by Erwin Haver (Fig. 8-24, plastic laminate, top, 1978-83) differs radically from Sculpturesque Young Hawk in Stone by Richard O’Hanlon (Fig. 8-25, above )

Carved-stone shapes of Monkey (Fig. 8-28, 1939, top) by J. Flannagan and Happy Landing, by A. Goodelman (Fig. 8-29, above) appear more massive than their modest physical dimensions.

Stoneware clay (Terra Cotta) is used by Betty Davenport Ford to create almost life size Reclining Gazelle (Fig. 8-32, top) and Puma (Fig. 8-33, above) which entail both additive and subtractive phases.

Pottery Bull of Persian origin (Fig. 8-37, 1,000 B.C.) demonstrates communicative power of primitive icon fashioned from Terra Cotta.

“Minimalist” values inform Reg Butler’s 18 in.-high Woman Standing (Fig. 8-41, 1952, left) and Kohlmeyer’s humorous polychromed Holy Man I (Fig. 8-42, right).

While Rodin’s Bur ghers of Calais (Fig. 8-43, top, bronze) required complex “indirect” process, narrative Deposition by Barbara Lekberg (Fig. 8-44, above, welded steel) achieved “narration” by “direct” process.