The Evolution of Style

Vanity of an Artist’s Dream by Charles Bird King (Fig. 11-1, American/ c. 1830) summarizes the artist’s befuddlement before a welter of stylistic influences.

The fact that the term “Style” refers to individual traits of a single artist as well as characteristics evolved over centuries by an entire culture, makes generalizations about one of the more important aspects of art problematic.

It may be precisely because of his virtuosic evolution from Blue Period to Rose Period to Cubism, etc. that Picasso achieved notariety during his lifetime. Change of style, in the case of such a virtuosic imagination, gives evidence of powerful creative energy.

In contrast, what significance shall we attach to periodic shifts in stylistic direction by cultures: Egyptian, Greek, Medieval, Renaissance, American? Historians of Western art have generally not regarded the ebb-and-flow of stylistic language as revealing significant insights about the maturity, vitality or stability of cultures.

“Standard art history” views stylistic ground-swells as observable phenomena, but rarely relates such phases of culture to that culture’s morphology: its evolution, for example, from nascent forms (“primitive”) to integrated expression (“classical”) and later sensuous preoccupation (“baroque”). Yet sometimes it is extremely useful for a student of art history to be able to extrapolate from one cultural milieu to another, finding trends that seem bigger than any manifestation in a single historical setting.

This concern has been recognized by isolated voices of the past (a French doctor, named Elie Faure in the 19th century, and Andre Malraux in the 20th, for instance). But my concern is that students in colleges and universities today are schooled largely to recognize stylistic traits (the names of the trees), while the revelatory ecology of the forest (cognate attributes across cultures) languish in obscurity.

Fig. 11-3 compares three stages of Medieval Style, reflecting changes in “levels of consciousness” described in theoretical-construct advanced by Dr. Alois Schardt.

Manifestly, not all stylistic insights have profound historical significance, for some are principally windows on national or ethnic consciousness, others merely the result of a unique congruence of technological breakthroughs and social change.

Previously, in our Insider’s tour of the art world, we have referred to Style in context of issues such as aesthetic preference, geographic bias, religious or political outlook, an artist’s motivation or some related variable in a complex cultural transaction (See “Introduction and Prologue”). In Chapter 11, Style itself will be our primary focus, with our initial thrust concerning ways in which we might grasp patterns of growth with potential to enrich and inform our appreciation of art of almost any epoch or culture.

In the development of distinctive artistic language, taste, whether that of an individual or an ethnic group, usually evolves gradually over time. The possibility that there are some innate human tendencies involved in that historical evolutionary process is among the richly-intriguing caches of cultural knowledge we are privileged to scrutinize, thanks in large measure to modern photography and communications. An absence of judgmental energy is important here, however, just as the psychologist dispassionately differentiates between adolescent, adult and geriatric behaviors.

Fig. 11-4 (left, det. above) reflects “Pre-conscious” quality of Old Kingdom Priest (Ranofer, 5th Dyn.) as compared with 12th-Dyn. Pharaoh, Sesostris III (Fig. 11-5/ right, with fragmentary portrait above). Note introspective gaze of Middle Kingdom, implying “Conscious” culture, along with loss of sanguine optimism of the earlier perceptual work.

The author’s personal odyssey into art history began in the 1950s with an opportunity to study with a German scholar, Dr. Alois Schardt, at the Claremont Graduate School in California. Dr. Schardt had fled Germany during the run-up to WWII, sensing an impending cultural debacle based on emerging reactionary tastes in art. Under his tutelage, I began to piece together a view which attempted to integrate the development of individual artistic evolution with insights relative to cultures in which artists might be embedded.

The center-piece of Alois Schardt’s philosophy of art, so far as I could discern it, hinged on his conception of “whole-consciousness.” An elusive concept, but nonetheless a critical one, in my opinion, whole-consciousness appears to be vested (physiologically) in the “right brain,” where humans apparently possess an innate “pre-intellectual” or intuitive capacity to formulate symbols perceptually.

Recent science has added substantially to our understanding of the physiology of the “left brain — right brain” dichotomy, but its significance here lies in Dr. Schardt’s belief that development of left-brain, analytical capacity in the later stages of culture renders more difficult the artist’s challange to achieve a unified vision. Conceptual art, in his view, often succumbs to analytical concerns above integrative impulses, overpowering the perceptual (sensuous and intuitive) whole on behalf of dissociative parts (largely intellectual).

Synthesis of observation and ideal in portrait of Thutmose III (Fig. 11-6, ca. 1436 B.C.) signals “Classical” era, often the threshold of an imperial epoch.

Over against that insight, Schardt posited the belief that intellectual development brought with it inevitable technological refinement (conceptual solutions to problems of material and design) which acted as a “counter-weight” to diminution of early, instinctual sensibility (whole-consciousness). Thus, somewhere in the development of cultures, Alois Schardt felt there was a “moment of GREEK ART synthesis,” in which early, instinctually-wholistic symbolism was balanced with developing technological (intellectual) prowess. In that ephemeral moment, we typically express the synthesis as “Classical,” whether in Egyptian sculpture, Greek pottery, Medieval architecture, or Renaissance painting.

In this vein, a Greek artist such as Exekias, or later Phidias or Polycleitus, can be seen as “Greek consciousness expressing in the moment” . . . almost a barometric-reading on the maturation of Greek society in that cultural instant.

From this perspective, when a modern museum-goer experiences the “power of Primitive art,” it would seem they are vicariously enjoying the “intuitive certainty” of a pre-intellectual era. And, if Alois Schardt was correct in his hypothesis about the morphology (patterns of growth) of cultures, we must also assume that from that wholistic,“Primitive” power there is an almost organic evolution, fueled by social and technological development and an increasingly analytical culture, to Classical forms and finally to aesthetically and emotionally-expressive outcomes in later stages. In some measure, one also finds this paradigm replicated in the life of an individual artist -as we shall attempt to demonstrate later.

Image of Queen Nefertari adorns shin of huge statue of Ramases II at Luxor, (Fig. 11-9, above) a contrast to parity of Queen Nefertiti in Fig. 11-8 .

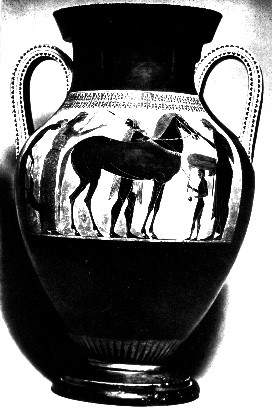

When we previously discussed aspects of the artist’s motivation (Chap. 4), we made a comparison of three stages of an evolving Mediterranean pottery-style, noting development from early “plastic” structure (a) to Classical “literary” idealism (b), and finally to “decorative” excitement in (c). The rugged, tactile form of the Mycenaen (or Proto-Greek) Griffin-head Jug (a) has Primitive energy, while a piece by Exekias (b) in the mid-6th cen. tactfully “adapts” a decorative frieze to contours of the Black-figured pot (Classical balance). Later, the Red-figured painter (c) is consumed with pathos in his narrative decoration, which totally dominates the enlarged body of the pot.(Fig. 11-2)

Noticeably, in this small sample, the trend has been from tactile to visual, from perceptual to conceptual, from symbolic imagery to more linear and descriptive forms. Static designs become increasingly fluid, and “limited space” of low-relief gives way to illusory space in which heightened pathos becomes feasible.

For Alois Schardt, a significant metamorphosis in this historical reenactment from culture-to-culture was the inevitable shift from anonymous craftsmen of the early stages, to identifiable artists of maturing societies, and “masters” of the later epochs. This phenomenon is congruent with what he described as “development of ego-consciousness during twilight of the Classical age(s) of Egypt, Greece, Medieval times (particularly in the West), and the Renaissance. observer’s visual perception of spiritual change, from a period of implicit faith in verities of the society (idealism), to a period of doubt (conflict) and later uncertainty reflected in self-conscious “personality” of portrait images.]

See, for example, the comparison of two Greek Funerary monuments, the famous Hegeso Stele (Fig. 2-18, 410 B.C.), and the similar Stele of Demetria (Fig. 2-19, 394 B.C.). Though separated by less than twenty years (and the initiation of a brutal civil war), the latter work projects a very different ethos to the viewer*:* the sublimely-reflective mood of Hegeso is supplanted in Demetria by an uneasy theatricality, suggestive of self-consciousness or ego-awareness.

“Ego-conscious” demeanor characterizes portraits of Priest from 7th cen. B.C. (Fig. 11-12, left) and Ptolemaic era (Fig. 11-13, right). One experiences individuated “personalities” on a level not acceptable even in political icons of the era of Ramases II (Fig. 11-10).

In order to further broaden our sampling of stylistic change in evolving cultures, let us now look at samples from a Medieval context: on the following page the reader will find images from a) a Romanesque setting in Parthenay, France in the 12th century, then b) a figure from Chartres Cathedral dating from around 1150 A.D., and finally, c) an image of John the Baptist from the Gothic Cathedral at Rheims in the 13th cen.

The 12th-cen. Romanesque head of Christ from Parthenay (Fig. 11-3a) evidences significant “archaisms” noted by Alois Schardt: Perceptual unity, observing wholistic-mass rather than separate features, conventional (i.e. eliptical eyes), tactile emphasis, etc. This work fits Dr. Schardt’s description of the Pre-conscious state, with marginal sentience of an iconic symbol of agrarian Medieval social order.

The Royal figure from the West Portal of Chartres (Fig. 11-3b, about 1150 A.D.), however, begins to stir inwardly (Conscious phase), and rudiments of “naturalism” appear in features and clothing. We commence to see a somewhat more delicate balance between “drapery” and the physique beneath, between tactile interest and the subtle surface rhythms which point the way toward more decorative (visual) and conceptual treatment of later Gothic forms. This “Classical” conception expresses stoic idealism, with little or no hint of “personality.”

Not much more than a half-century after the Chartres figure, we find an image of John the Baptist from the facade of Rheims Cathedral (113c) which ventures into the realm of personal emotion: compassion, perhaps, but with its knitbrow and demeanor of sadness, a harbinger of egoconsciousness arising in mature Gothic style.

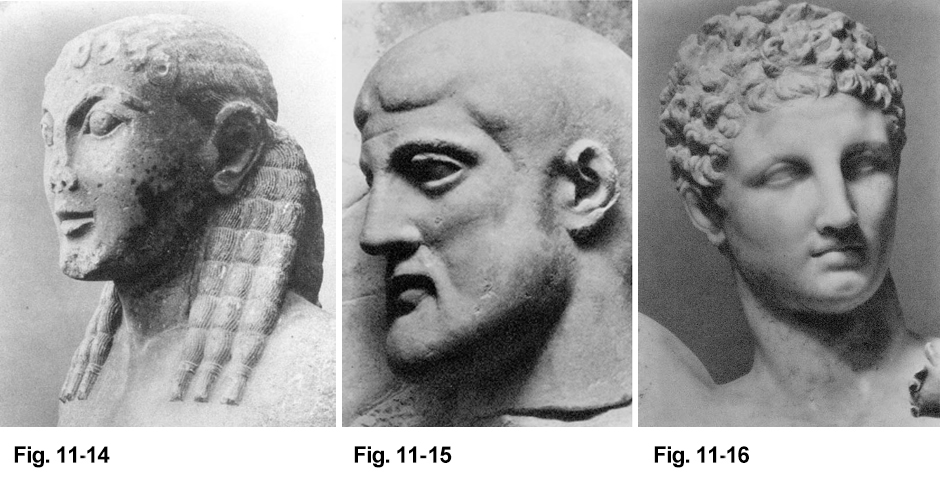

Stylistic evolution in Greece can be experienced as shift in “level of consciousness.” At right, from top: Fig. 11-14, Archaic Kouros, Cleobis, 582 B.C.; Fig. 11-15, Hercules/ Olympia, 2nd quar. 5th cen. B.C.; and Fig. 11-16, Hermes by Praxiteles, 350 B.C.

Is such an historical-analysis (in terms of levels of consciousness) “inevitable?” Probably not, but as we go on and inquire whether this “thesis” has relevance in such an era as Dynastic Egypt, you may begin to sense that Alois Schardt offered us a fecundating prism through which to more-clearly grasp the rhythms of human experience.

One would hardly conceive of stone sculptures of Egypt reflecting disparate levels of “consciousness.” Among profound mysteries of Egyptian lore is the absence of any substantial “Primitive phase” in the hieratic art which anticipated the estimable achievements of the 3rd, 4th and 5th Dynasties of the Old Kingdom. Later, political incursions of the Middle Kingdom disrupted evolutionary processes, making continuity with the earlier period problematic.

Components of Dr. Schardt’s model can be seen in the earlier portrait of Ranofer (Fig. 11-4), which still relies more on conventional geometry than on individuated expression. The figure is erect, appears to represent unquestioning faith in the Pharaonic system (i.e. the “God-King” concept) of the Old Kingdom, and bespeaks a simple, agrarian stage of culture (Pre-conscious, or based largely on tradition).

The Middle Kingdom image of Sesostris III (Fig. 11-5) is the product of a later, feudal society, forged out of conflict, and expressing Consciousness and worldly sadness. The physique lacks vigor of its earlier counterpart, is more highly descriptive and less “ideal.” It is well to remember that this is “funerary” art, and was intended solely as eternal resting-place for the Ka, or soul of the deceased.

The Middle Kingdom image of Sesostris III (Fig. 11-5) is the product of a later, feudal society, forged out of conflict, and expressing Consciousness and worldly sadness. The physique lacks vigor of its earlier counterpart, is more highly descriptive and less “ideal.” It is well to remember that this is “funerary” art, and was intended solely as eternal resting-place for the Ka, or soul of the deceased.

After the chaos of the Middle Kingdom and ravaging of tombs during a lengthy occupation by Hyksos invaders from Syria and Mesopotamia, it was almost 400 years before Egypt recovered autonomy under King Thutmose I. His daughter, Hatshepsut, would later ascend the throne as “Pharaoh,” following the death of her half-brother, Thutmose II, to whom she was married at age 12.

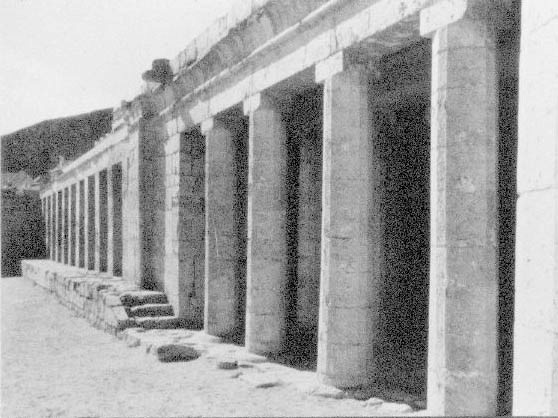

Mystery still surrounds the 18th Dynasty “Renaissance” of Queen Hatshepsut, who, between 1479 and 1458 B.C. inaugurated a remarkable “Classical synthesis” in Egyptian architecture (Fig. 11-7). Unfortunately, much of her legacy was posthumously desecrated by her stepson, Thutmose III (Fig. 11-6), for whom she earlier had acted as “regent” (and some historians might add, usurper).

Queen Hatshepsut informed her rock-cut Funerary Temple complex at Deir el-Bahri (Fig. 11-7, before 1450 B.C.) with a profound sense of human scale. Likely influencing Greek taste a millenium later, her chamfered columns complemented rather than intimidated, unlike those of her successors (e.g. Ramases II of the 19th Dynasty). Some of her “mannish” effigies were nearly ten feet in height, however, and survived the subsequent rule of Thutmose III as buried fragments.

Classical poise informs The Mediterranean, as early as 1902 (Fig. 11-29, left), whereas late work known as The River, 193943 (Fig. 11-30, right) suggests spatial exhileration and visual treatment of hair-locks consistent with “late” performance.

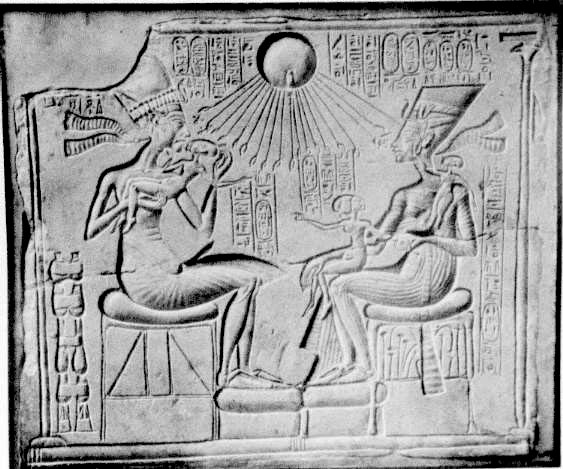

By early decades of the 14th century B.C. a revolutionary combination of imperial ambition, aesthetic rebellion against past rigidity, and religious conversion of a monarch, Amenophis IV, conspired to set Egypt on a radical Monotheistic experiment.

Known as the Amarna Period, this brief “official” departure from conventions of frontality, immobility and formalism attempted unsuccessfully to reform Egypt’s religious and political hierarchy. Amarna replaced Thebes as the seat of priestly power, and Egyptian establishment-art embraced a lyricism (Fig. 11-8) which had previously been known (as far back as the Old Kingdom) only in Folk Art productions.

The “Rebel-King,” Amenophis IV (who changed his name to Akhenaton, in honor of his new diety, Aton) also fleetingly redirected Egypt’s official art from its focus on immortality. Instead of its exclusive concern for survival of the Ka after life, “official art” of the Amarna Period pictured the regent and his family frolicking beneath benign rays of the Sun-God, Aton.

”Early” Moore Reclining Figure (Fig. 11-32) suggests eclectic influence of tactile/perceptual Pre-Columbian Style on artist’s developing aesthetic.

Stylistically, one would be hard-pressed to recall an instance where visual language of a culture has reversed itself so abruptly: from spatial rigidity to a fluid naturalism, from preoccupation with death to affirming life, from static tactile forms to highly visual and linear expression. Following Akhenaton’s death in mid-14th cen., however, all traces of his reign were obliterated by the dispossessed priests of the “old-God,” Aten. Amarna was abandoned, and the pendulum soon swung back to repressive religion and imperial politics. Under Ramases II (Fig. 11-9) of the 19th Dynasty (mid13th cen. B.C.), official art became a tool of “public relations,” rather than a spiritual window on eternity.

There is remarkable vigor in the portrait of Ramases II in Fig. 11-10, with highly conceptual treatment of particulars such as features, visually complex headdress and especially the “power symbol,” known as a Baselisk. Occasionally, colossi (such as the effigy at Luxor, Fig. 11-9) retain a measure of early tactile conviction of the Old Kingdom. But more often, bloated scale of architectural sculptures such as Abu Simbel (and much of Ramases’ temple construction) places crushing weight on the human spirit.

Two additive works from the 1950s, Internal and External Forms (Fig. 11-34/ far left, 1953-54) and Draped, Seated Woman (Fig. 11-35/ left/ 1957-58) evidence a significant (Baroque) trend toward size, movement and visual effects.

It is notable that we are not apt to encounter what Schardt terms “ego-consciousness” here, however, for it is not until roughly 600 years later, during what is known as the Saite Period that we find a “self-conscious” vein surfacing to a significant degree (Fig. 11-12). As the old verities failed to accomodate reality, perhaps an infusion of non Egyptian cultures from its borders in the 7th cen. B.C. brought angst, along with tensions of Greco Roman influence (Fig. 11-13).

In little more than a cursory way, we have tested the “Schardt thesis” for its applicability, first to Medieval (Romanesque and Gothic) forms, and then to the complex tradition of ancient Egypt. It seems only fitting now to reference Greek experience before we pass on, and then we might look at how individual artists have sometimes followed similarly-predictable stylistic-evolution starting with the Italian Renaissance.

For purposes of continuity, I have chosen three Greek works from roughly the “stages” we encountered in the Medieval sample, although the later piece in this selection is somewhat more “developed” (aesthetically) than the Gothic image of John the Baptist from Rheims.

Forty-six-foot Monolith (Fig. 11-37/ left), depicting human aspiration and cyclical nature of life, was carved in part during Nazi occupation. Stone groups in inset reveal “narrative” quality and pathos, but don’t suggest “self-consciousness.”

“Pre-conscious” aspects of the Doric Cleobis portrait (Fig. 11-14) seem in significant ways similar to those of the Parthenay Christ (Fig. 11-3): geometry triumphs over descriptive naturalism (conventional hair treatment, eyes, etc.), and there is a kind of “primitive energy” in both. Of particular notice in the “Archaic” Greek work is the presence of what art historians call “the Archaic smile.” Conspicuously-absent in the Medieval image from Parthenay, it is thought to be an acknowledgement of a pre-intellectual sense of well-being, or faith in the verities held by the culture of origin.

A “Conscious stage” in Greek development comparable to the Chartres figure in Fig. 11-3 might be such an image as that of Fig. 11-15, the head of Hercules from a Metope carved for the Temple of Olympia in the second-quarter of the 5th cen. B.C. Retaining some earlier (Doric) tactile and perceptual qualities, it seems clearly a representation of sentience and moral force, verging on early descriptive naturalism ventured centuries later by the Chartres stonecarver.

The third Greek selection (Fig. 11-16, Hermes by the Hellenistic sculptor, Praxiteles) lies somewhere near the realm of “self-awareness,” but it would seem to me inappropriate to term this work “ego-conscious.” Praxiteles has gravitated far beyond the

Contrasting technique differentiates two works attributed to Vermeer: The Procuress, 1656 ( left, Fig. 11-41) and Officer and Laughing Girl, (right, Fig. 11-43). Details reflect stages in stylistic development. In Fig. 11-42, (inset, left) objects are solid, opaque (Reality of the Eye), while in Fig. 11-45 (inset, rt.), light transmutes “physical elements” into purely metaphysical reality.

balanced Classicism of Polycleitus a century earlier (see Fig. 1-39) to effect an image both highly visual and less virile than the former (more influenced by Ionian taste). The expression, “veiled emotion,” has aptly been used to describe the Praxitelean canon of masculinity, but there is no inference of introspection here, so far as the writer can observe. With proportionately smaller head than earlier kouros figures (male prototypes), Hermes is nonetheless an “ideal” of Greek manhood for his time, universal in all respects and not in evident possession of introspective tendencies. Therefor, it would seem this work is not an example of “ego-consciousness” in the Schardt canon.

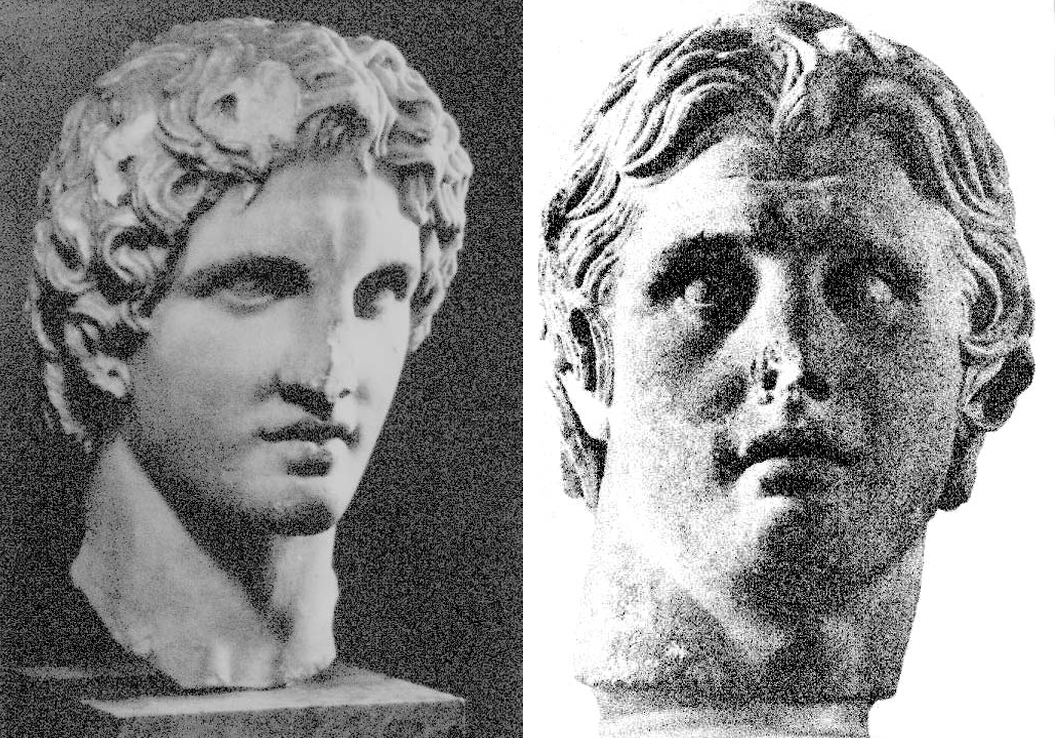

Two portraits of Alexander the Great, however, would appear to delineate the threshold of universality (Classicism) as opposed to ego-consciousness — both from about the same period of Hellenism as the Hermes. In Figure 11-17, Alexander would seem to possess no conspicuous “personal emotional baggage.”

The rendition of Alexander the Great in Figure 11-18, however, appears to represent a later stage in his imperial imbroglio — a period fraught with angst and a consciousness of mortality (ego-consciousness). His knit brow and deep-set eyes would suggest an awareness that all was not well in the Hellenic world.

Vermeer fuses light from casement with brushwork describing iconic figure in Fig. 11-44.

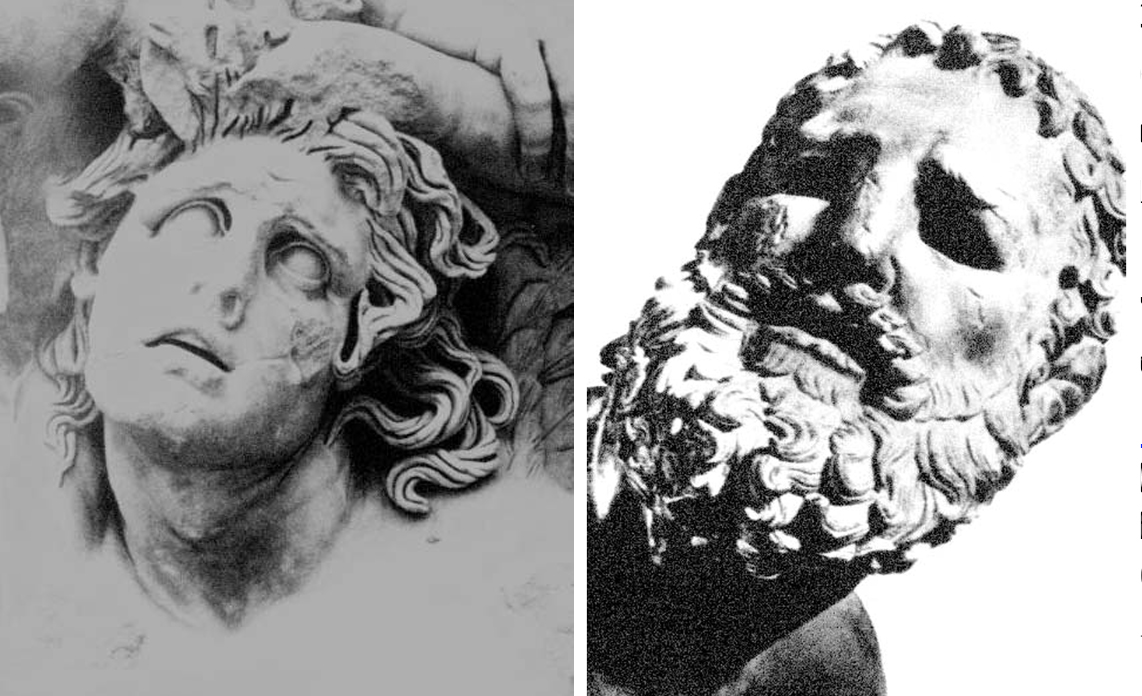

We earlier noted the expression of _personal pathos_ in Red-figured pottery decoration of the 1sthalf of the 5th century B.C., but in monumental Greek sculpture, it only becomes fairly common by the late-3rd century B.C. (Figs. 11-19, 11-20).

Perhaps it would be useful at this point to suggest some additional “evolutionary factors” which generally coalesce within the Schardt viewpoint on cultural change. His “critical language” was rich and varied, covering even a greater range of variables than those listed overpage.

Some Factors in the Evolution of Culture / Style / Perception

Among tantalizing questions art historians ponder is the relationship between maturational patterns of cultures and the development of individual artists who enjoy long and productive lifetimes. Such Renaissance luminaries as Donatello or Michelangelo, for example, or Modern giants such as Britain’s Henry Moore, Aristede Maillol of France or Gustav Vigeland of Norway appear to follow somewhat the same aesthetic pathway as did the ancient Greeks or Medieval craftsmen.

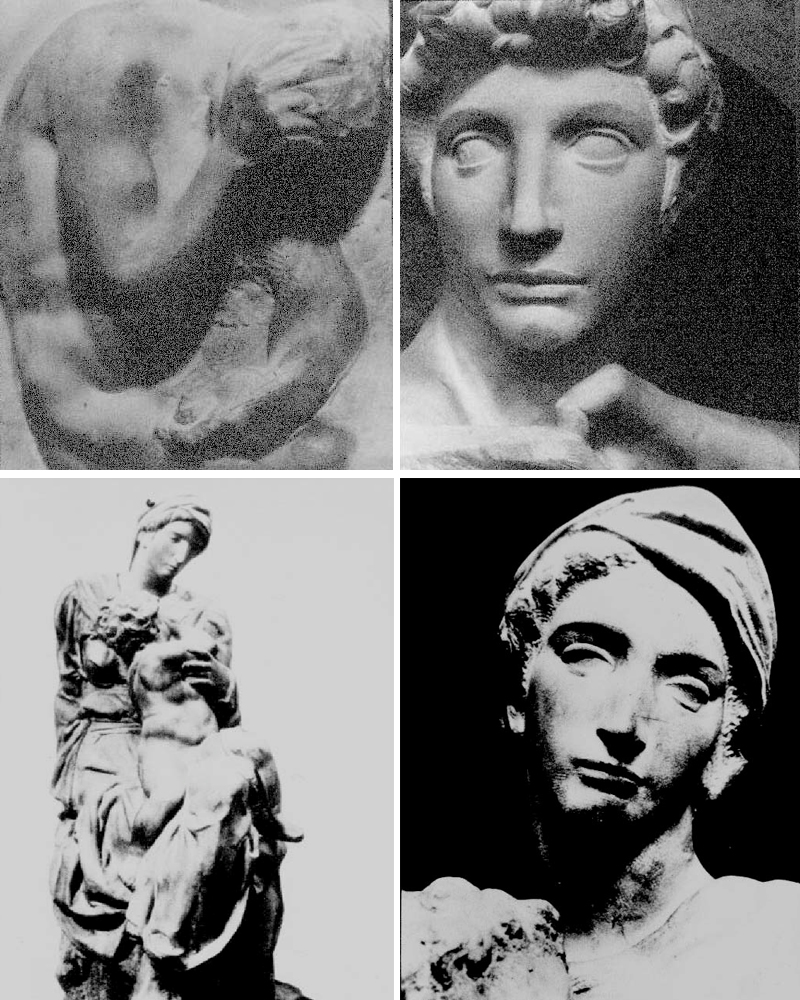

In Chapter Eight we compared some “early” and “late” works of Ghiberti and Donatello — noting characteristics associated with phases of their careers. It might thus be instructive to look briefly at sculptural works of Michelangelo, a generation later, to see if any of the same aspects recur.

You will note in Fig. 11-21, which is considered a “juvenile” work of the young Michelangelo, that a number of traits of the preconscious state obtain: preeminent tactile interest in a low relief medium; absence of obvious conceptual elaboration; “primitive” energy. In “The Victory” of 1519 (Fig. 11-22), much of that physical zeal persists, but now increasingly tempered with a developing Classical idealism. Features are conventional and anatomical forms broadly generalized.

Vermeer’s Maid Pouring Milk, 1660, achieves Classical qualities of balance and immobility, combined with highly tactile handling of form, pigment and lighting effects. (Fig. 11-46, far left and details). Note “pebbly” texture.

Then, in features of the Medici Madonna of 1525-34 (Fig.11-23 & 11-24) one might discern a somewhat more “Tuscan” character (more rugged than ideal), with less Classical detachmant and a decidedly “unclassical” twist in the torso of the Child.

Following completion of his second stint at the Sistine, in the spatially-complex Florence Pieta (Fig. 11-25) we sense a “frontality” that doesn’t exist in the Medici composition, and a growing conceptualism in development of the elaborate pyramid of forms which (it is conjectured) he topped with his own visage.

The Rondanini Pieta (Fig. 11-26) from the last decade of Michelangelo’s life, is admittedly the work of a febrile hand, but its moodiness and painterly surface-treatment seem nonetheless to be a matter of Masterly intent, not of default, and could appropriately be compared to Rembrandt’s last self-portrait, in my judgement.

It is doubtless presumptive to attempt to “capture” the evolutionary development of any genius of the magnitude of a Michelangelo in capsule form. But the question persists: Given historical pressures (such as wars and patronage) does an aging creative individual nonetheless manifest some of the same qualities over a lifetime as did, say, early Greek culture?

Homer’s Prisoners from the Front (Fig. 11-47, 1866) reflected Northern need for information about progress of fratricidal war.

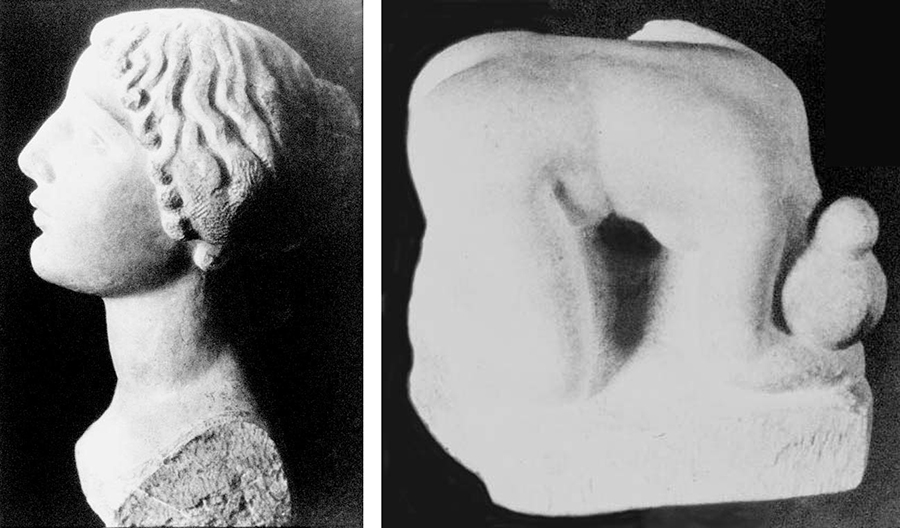

In a 19th- and 20th-cen. context, we might take a brief look at the work of the French Master, Aristede Maillol, from a maturational viewpoint. One finds a perceptual/tactile bias in some of his carved work, such as Fig. 11-28, Crouching Figure. Massive and static as well as space-shy, this piece has much in common with Primitive works of many cultures. Head of a Woman, (Fig. 11-27) also shares conventional treatment of anatomical features with Archaic Greek Kore archetypes.

As early as 1902, however, Maillol gravitated toward a Classical ideal in his now-famous Mediterranean (Fig. 11-29), which exhibits crisp geometric coherence and a contemplative restraint. Then, by 1939-43, his interest in kinetic expression, tensile properties of materials, and visual articulation of flyinghair edged-out “restraint” in his eloquent metaphor, The River (Fig. 11-30).

Indeed, one might compare the radical Greek Nike of Paionios at Olympia (Fig. 11-31, 421 B.C.) with Maillol’s dramatic conception. Both exploit space in a virtually unprecedented manner, suggest celebration of feminine physical charm as a cultural value, and would seem to venture close to the Baroque stylistic rubric which embraces temporal as opposed to “timeless” statements. The Olympia Nike would appear to be a “bronze conception,” precarious and virtuosic carved in stone, whereas The River by Maillol was hollow-cast in lead to permit its spatial elegance.

Homer’s early experiment with Impressionism (Long Branch, N.J./ Fig. 11-48/ 1869, with detail) failed to divert him from a primary concern for “natural” light and form.

In Chapter 2, we discussed some significant phases in the career of Henry Moore. Though Moore, to my knowledge, never produced what Alois Schardt would categorize as “self-conscious” art, a further look at his development may nonetheless validate Schardt’s historical model.

It is not hard to substantiate the “Primitive” leanings in Moore’s early glyptic efforts. Exposed to PreColumbian carvings at the British Museum, he produced a number of static and perceptual works such as Fig. 11-32, Reclining Figure in stone.

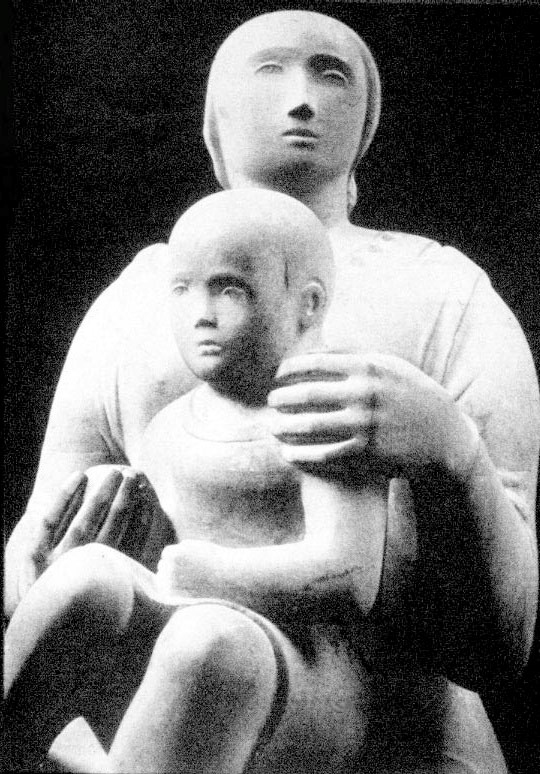

By 1943, as Britain withstood cross-channel rocket-attacks, I would have no problem with categorizing his serene Madonna and Child, carved in Hornton Stone (detail, Fig. 11-33) as “Classical” in its restraint and balanced idealism. A growing naturalism replaces the iconic primitivism of earlier experiments.

By the 1950s, Moore’s Post-War “draped figures” in bronze (Fig. 2-30) invoke the cosmopolitan “ripeness” of Phidian marbles of the Parthenon (Fig. 2-32), and later in the decade, Moore was also moving in the direction of greater size (Fig. 11-34). Having abandoned “Classical balance” for a spatially-complex “dissonance,” his Draped, Seated Woman in New Haven (Fig. 11-35) appears to be “unsupported” by her stone bench, and her deeplyetched drapery and diminutive head (cf. Lysippus and Hellenism) link her with “late” Greek consciousness.

Study of Tynemouth Beach (Fig. 11-50, 1881/ left) in England was part of extended “immersion” in marine environment, which flowered into seascapes without figurative element (Prout’s Neck, Maine, Fig. 11-49, 1883/ right).

With the less-well-known Gustav Vigeland (Norway, 1869-1943), developmental stages are somewhat more difficult to trace, because, like Ghiberti, he gave a major portion of his career (36 years) to one project — Frogner Park in Oslo. Both Gustav and his younger brother, Emanuel, were proteges of Auguste Rodin in Paris in 1892. Eventually, the elder brother created 192 sculptures (600 “nude figures”) outdoors — expressing virtually every human condition, while the younger brother left as his legacy a brooding tapestry of fresco painting and bronze sculpture in a mausoleum which seems a blend of Rodin’s Gates of Hell and Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights.

Like Moore in England, Barlach in Germany and Raemisch, who fled to America, the Vigelands coexisted with the Nazi phenomenon; in addition, the brothers were raised by an alcoholic and abusive father.

The work at Frogner Park covers the gamut of emotions: from abuse to affection, from joy to rage and from birth to senesence. Pathos is in abundance here, but often (as with the 46-ft. monolith erected during the waning days of Nazi occupation in Norway), no judgment seems involved – just observation!

We have discussed “primitive aspects” of his stone-carving, The Family (Fig 5-15) -static, tactile, conventional, space-shy, perceptual, “whole-conscious.” This group was one of a number of glyptic compositions with which the sculptor leads one toward the stark granite centerpiece of his Baroque plaza. Vigeland appears to have consigned the carving of 121 naked adults and children depicted in the central column to three stonecarvers who labored from 1929 to 1943. Perhaps Rodin’s firm commitment to “realism” influenced the “mundane” aspect of these and indeed most of Vigeland’s other figures, for one finds the Mediterranean aspect of “idealism” almost entirely supplanted here by Nordic existentialism (in stone) and exuberant kinetic expressions (in bronze).

In the later bronze group, Two Boys Running (Fig. 11-38 about 1928) for a bridge-parapet, we experience ebullient spatial and kinetic energy which celebrates “unclassical” values of spontaneity and visual excitement. That “Baroque” duality is also presenting Mother and Child (Fig. 11-39, 1928) where there is pathos as well as delight in linear expressiveness of Mother’s hair. The latter is reminiscent of Maillol’s roughly contemporary work, The River (Fig. 11-40, detail; also Fig. 11-30), similarly a “late work” of that artist.

“Classical Homer” depicts heroic figures with development of tactile volumes and restrainted color (Undertow, 1886/ Fig. 1153 and inset).

If certain similarities of aesthetic development do exist between sculptural traditions of the past and individual sculptors from Ghiberti and Donatello to Moore, Maillol and Vigeland, dare we consider a possible parallel among “giants” of visual as well as tactile art?

Dealing, as we have, with artists whose principal output was haptic, rather than visual, it is improbable that we could extrapolate from our limited sampling of individual artist’s sculptural development to compare visual artists’ morphology. Obviously, any “congruity” of style among painters would likely differ significantly from those historical patterns suggested in our review of the work of Alois Schardt.

Not surprisingly, however, in looking back over the annals of Western painting tradition, we can surely find ample evidence of “primitive” characteristics in Proto-Renaissance masters such as Giotto, Uccello, and later, even Piero della Francesca (painters who searched for descriptive language informed by a venerable Mediterranean tradition of relief sculpture).

Their “tactile essays” were soon followed by a “Classical” synthesis (balance, formal concerns, restraint, etc.) in the likes of Botticelli, Giorgione and Raphael.

Then, almost inevitably, concerns with spatial experimentation, dramatic lighting and movement captured the imaginations of artists such as Mantegna and Tintoretto — setting the stage for Baroque and Mannerist expression in Spain, Flanders and Holland, as well as Italy.

This story has been amply told and is not the purview of our present discussion. However, I do believe there is fertile ground to be explored in tracing some parallels between this evolution and the stylistic maturation of Masters as diverse as Giorgione, Botticelli, Rubens, Vermeer, Rembrandt, Degas, Manet, Winslow Homer and Andrew Wyeth, to name a few.

The thesis I would advance suggests that these and other Masters often begin a career “describing reality”(literary motivation), only to move on to more “formal concerns” (plastic preoccupation over-riding the descriptive). As a “crowning” of this formal,“Classical phase” the artist’s “mature expression” begins to transmute reality into light/ color/ pigment, with little concern beyond creative process — the painting medium and metaphysics. Final works are no longer representations of things, but of states of consciousness.

Unfettered by the triumph of Impressionism abroad, Homer eschews both brushstroke and figurative intrusion in later oils of the Maine coastline: Fig. 11-54, Moonlight, Wood’s Island Light/ 1894, top, and Fig. 11-55, Maine Coast/ 1896.

To initiate this “unscholarly” examination of “aesthetic history repeating itself,” let us make a cursory scrutiny of works by the Dutch Master, Vermeer. His canvas, The Procuress (Fig. 11-41, 1656), embraces a Northern descriptive tradition that goes back to the Van Eycks. The inset detail of glass, decanter and hand(s) (Fig. 11-42) conveys a robust mix of visual and tactile stimuli which the author would characterize as “Reality of the Eye.”

In contrast, two details of Fig. 11-43 (Officer and Laughing Girl, mid-1660s) suggest a later development, as Vermeer depicts the figure of a young woman (Fig. 11-44) flooded by pellucid lighting from an open window, virtually transmuting her into a Gothic icon. Light invades matter (see Fig. 11-45) in a synthesis with crystal, flesh and fabric, wherein the alchemy of pigment and brushwork obscure optical reality on behalf of metaphysics (Reality of the Mind).

Vermeer’s 43-year life-span was brief in evolutionary terms, but one can nonetheless see significant changes in his stylistic treatment of the Dutch interior. For example, in Fig. 11-46 (Maid Pouring Milk, c. 1660), one might well sense a “bridge” between Vermeer’s handling of pigment and light in Fig. 11-41 (fairly “prosaic” description) and the more esoteric mixture of elements in Fig. 11-43 (where one sees light fused with matter, much as in rich glass mosaics of Byzantium – metaphysical icons which venture to depict the “heavenly.”)

In Fig. 11-46, which for want of a less-pretentious term, I am dubbing a “Classical” synthesis of tactile and visual interest, static composition and natural, descriptive light, one experiences a Master in full control of his medium. Maid Pouring Milk is eminently rational in its handling of light, and neither pigment nor brushstroke ventures toward dematerialization of solid, mundane forms.

What is added in the later stages (e.g. Fig. 11-43) is an almost “mystical” transformation of the artist’s medium into aesthetic description of a metaphysical reality. Light and/or color at that moment serve to communicate the ineffable — what words cannot.

We have noted these epiphanies along the way in works of such diverse practitioners as Roualt (Fig. 10-34), Monet (Fig. 9-28), Rembrandt (Fig. 9-9), El Greco (Fig. 1-23), Rubens (Fig. 9-7), to name a few. And it seems likely that a review of the oeuvre of any of these giants would reveal a pattern of growth from 1) a “developmental,” descriptive phase to 2) “Classical” control of artistic elements, and 3) eventual identification of subject matter with substances of light, color and medium in which they worked. Patently, many artists do not achieve the mastery embodied in latter stages of this evolutionary process.

As an example of this developmental model, perhaps I will offer works of a less-internationally-recognized American master, Winslow Homer (1836-1910). As we mentioned in Chapter 4, Homer began his career as a lithographer and journalist, sending drawings of Civil War skirmishes to Harper’s Weekly. So it seems entirely natural that his early bent was descriptive (Fig. 11-47). We discussed two of his relatively-early paintings in another context (High Tide, 1870 and Snap the Whip, 1872), both of which evidence a strong literary impulse. Previously, following a trip to Paris, the artist had explored Impressionist style (Long Branch, N.J., 1869, Fig. 11-48), but it was not Homer’s nature to “dematerialize” figures and landscape and recreate them as “brushstroke,” in the French manner.

After spending much of 1881-82 in Tynemouth, England, Homer returned to the U.S., to embrace a reclusive habitat on the coast of Maine. Expressing his “liberation”at being on “native soil” once again, the artist produced seascapes without figurative or literary “mediation” (Prout’s Neck, Maine, 1883, Fig. 11-49). Comparison with one of his studies from Tynemouth (Fig. 11-50) points to growth of his confidence while abroad.

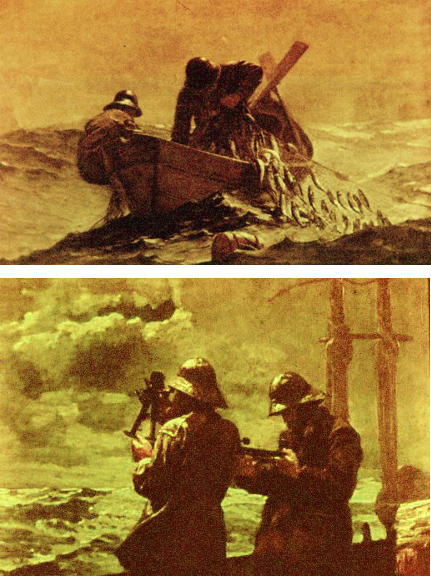

Two “mature” works (Fig. 11-51, Herring Net, 1885 and Fig. 11-52, Eight Bells, 1886) display a marked penchant for formal order and static balance (Classicism), as Homer discovered his metier in heroic scenes of marine life. In a painting entitled Undertow, 1886 (Fig. 11-53 and inset), one experiences the artist’s affinity for tactile values and idealization of the human figure, with little or no emphasis on chromatic effects or Transcendentalism.

The factor of patronage may be highly significant at this point in the artist’s evolution, since Prout’s Neck was remote from the galleries of New York and Boston (where John Singer Sargent was enjoying great success.)

It was in the mid-90s that Homer substantially abandoned literary (figurative) elements and finally began to explore a synthesis of light and pigment in tumultuous seascapes (Fig. 11-54, Moonlight, Wood’s Island Light, 1894, and Fig. 11-55, Maine Coast, 1896). American to his roots, however, Homer held firm to his sensuous experience of nature, rendering it almost entirely without Impressionists’ virtuosic brushstroke.

Ironically, when Homer finally indulged his passion for light and transparency, it was in the medium of watercolor, during the last decade of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th. His Adirondack Guide of 1894 (Fig. 11-56) allows the human figure a subordinate role in a mysteriously reflective world to which Homer escaped — while Impressionism and Post-Impressionism shaped American taste in other directions.

Two Homer works dealing with mortality and coming from the last two decades of his life (d. 1910) interestingly embrace rather Baroque celebrations of movement and spatial sensation. A Darwinian opus called The Fox Hunt (Fig. 11-58, 1893) reprises a theme of existential jeapardy suggested earlier in Fog Warning (Fig. 11-57, 1885) and again in The Gulf Stream of 1899. Right and Left (Figure 11-59, 1909) celebrates the artist’s life-long passion for hunting and fishing with a highly-kinetic image of falling ducks, that may suggest Homer’s grudging acquiesence in the growing trend toward a 20th-century-European assertion of the “picture plane” over illusionistic space.

Perhaps the absence of Transcendental aspiration in the work of Winslow Homer raises a question concerning his place in annals of great painters we have discussed to this point. However, the paradigm of “artistic development” suggested here is merely an approach to understanding stylistic morphology, and though it was patently not Homer’s nature to “dematerialize” painted form by fusing pigment, light and brushstroke in his late work, it would appear that his oeuvre conforms in many other regards.

(c) 470 -- 460 B.C. Three phases of Greek Pottery (Fig. 11-2, top) show stylistic evolution from early Mycenaen prototype (a) to Black-figured design (b), and culminate with Red figured Amphora (c). Pottery tradition evolved somewhat more rapidly than cognate sculptural style.

Human-scale of the Rock-cut Funerary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri (Fig. 11-7) perhaps set standard for later Mediterranean world.

Relief depicting Akhenaton and Nefertiti fondling three daughters (Fig. 11-8 ) suggests new social and theological climate of Amarna Period in the 18th Dynasty.

Ramases II gave Egypt imperial status in 19th Dyn., about 1270 B.C. (Fig. 11-10, top). Note prominence of Baselisk on forehead (symbol of power of life-and-death). Sixtyfoot collosi from Abu Simbel (Fig. 11-11, above) were relocated for Aswan Dam project.

Two renditions of Alexander the Great convey very different consciousness: Fig. 11-17 (left) is without emotional specificity, while Fig. 11-18 (right) displays pathos of “personal” anxiety.

Signs of individual pathos (ego-consciousness) are visible in image of Alcyoneus from Pergamon (Fig. 11-19, left, 200 B.C.) and battered Bronze Pugilist (Fig. 11-20, right, 211 B.C.)

Detail of relief, De Janira, by 17-yr.-old Michelangelo (Fig. 11-21, 1492/upper left) offers analogies to “Primitive style,” with “tactile energy” also informing 1519 carving, The Victory (Fig. 11-22/detail, right) along with Classical idealism. Later Medici Madonna (Figs. 11-23 & 11-24, 1525--34/det. bottom) reveals increased conceptual and spatial complexity.

Florence Pieta, 1550-56 (Fig. 11-25, left) invokes “personal” note (artist’s portrait), and expresses more “High Renaissance formalism” than later “Impressionistic” Rondanini Pieta’s tortured surface (Fig. 11-26, right).

Conventional treatment of Fig. 11-27, Head of a Woman, left, and “spaceshyness” of Fig. 11-28 (Crouching Figure) suggest Primitive ideal in some works of French sculptor, Aristede Maillol.

Nike of Paionios from Olympia (Fig. 11-31, Greek, 421 B.C., above) offers parallels to spatial excitation and physical charm of Maillol’s image, The River. This feminine ideal came toward the end of the Golden Age of Pericles, when rivalries exploded in fraternal conflict. Maillol’s image is congruent with initiation of W.W. II.

Moore’s Madonna and Child (det. Fig. 11-33) expressed “Classical calm” during critical war years in Britain (1943-44).

Among glyptic pieces surrounding monolith in central plaza, The Family (Fig. 5-15) displays evident inspiration from “Pre-conscious” sources: static, tactile, perceptual, space-shy, etc.

Bronze relief of Children Struggling (Fig. 11-36) from Fountain Complex, reflects tension between “timeless” statement of Mediterranean consciousness and “temporal” psychology of Northern perspective. Note also, Conscious (“Red-figured”) spatial orientation of boy’s figure.

Ecstatic movement and mastery of physiological expression (Two Boys Running, Fig. 11-38, bronze, 1928) suggest “mature” Vigeland manifested characteristics of Baroque style near conclusion of 36-year project.

Mother and Child (Fig. 11-39, circa 1928) offers somewhat conceptual solution to mother/child duality, as parapet decoration for Oslo bridge.

Movement, emotion and visual effects characterize Maillol’s 1940 metaphor, The River (Fig. 11-40, det.) a product of tempestous years of WWII.

Mature works of Homer’s 50s exhibit lingering penchant for story-telling, with strong admixture of plastic design (Fig. 11-51, Herring Net, 1885, top, and Fig. 11-52, Eight Bells, 1886, bottom.) Figurative elements balance oceanic backdrop, which has not yet become principal protagonist in his maturing style.

Absent both coastal scenery and oil medium, Homer in 1894 turns to watercolor for near-Transcendental fusion of transparent medium and vernacular subject. (Adirondack Guide, Fig. 11-56, 1894).

The hunter-and-the-hunted become ironic themes of the sportsman/painter (Fog Warning, Fig. 11-57, 1885, top, and The Fox Hunt, Fig. 11-58, above, 1893) as the artist ventures essays in space and movement.