The Psychology of Art

Art is expression, communication, soliloque or conversation. But always, it is psychology made manifest. Unless the artist has “something to say,” it is doubtful there would be an occurrence in which the average viewer might find significance.

Sometimes the artist is “in your face” with a viewpoint. In other circumstances, it may serve artistic ends for that viewpoint to appear elusive, even obsure. History has not always been kind to the outspoken, and much social and religious commentary has perforce been cloaked in subtle language accessible only to those armed with keys to interpretation.

A Self Portrait with Pencil (1935) by Kathe Kollwitz offers complex psychological stimuli involving us observing artist (Fig. 7-1 ) observe herself.

Chapter 6 dealt with many manifestations of a process we called “reduction” in the making of art — steps which inevitably trace a path from the mundane to the masterpiece. An awareness of issues of psychological content lies along that path, for the creator as well as for the ultimate viewer.

This chapter will look at the “tools of analysis” which have typically been helpful in assessing a viewer’s responses to an artist’s language, regardless of medium or cultural setting. Like psychology itself, art-forms such as dance, music, visual arts or theater can have subtle and at times conflicting messages for the observer. It enhances one’s capacity to experience those art-forms if one is familiar with psychological variables inherent in a particular medium.

In the charcoal self-portrait on the previous page by Kathe Kollwitz, we find ourselves (the viewers) studying the subject (Kollwitz) in the act of intently viewing her own hand, which (we are told) holds a pencil. The warm intimacy of the artist’s penetrating study of her profile and a fairly well-developed hand elicit feelings of familiarity from the typical viewer — but those feelings are abruptly modulated by introduction of haphazard “scribbles” of the charcoal medium across what would have been an image of her extended arm.

Portraits by Van Gogh ( Peasant Girl, Fig. 7-5/ left) and by Eakins (Addie, Fig. 7-6/ right) typically elicit sharply contrasting emotional response from viewer.

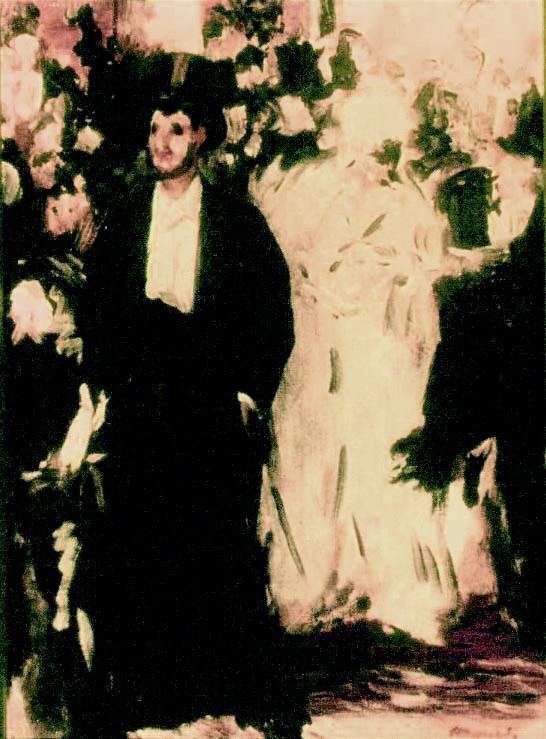

What is the artist “saying” when she radically upsets our expectations of continuity between head and arm? Is she saying something about herself (self-esteem) or about the ultimate value of her self-image as “art?” Does her slashing “gesture” with the charcoal-medium bear any relationship to Impressionist, Manet’s, brushwork in Ball Scene (Fig. 7-2), which asserted that spontaneity had triumphed over mere description? And, how does psychology play a part in this, one might ask?

If psychology is the study of human emotions, then the “psychology of art” would seem logically to be focused on the emotional impact of art works on the viewing public. As with certain people we encounter, artwork may interest us, draw us toward it in an empathetic manner. Or, a work with different artistic objectives may prompt us to distance ourselves, based on myriad qualities of style or technique artists employ to convey their reality.

Both Kollwitz and Manet would seem to have interposed radical manipulation of their medium as a distancing element, sacrificing traditional empathetic responses to their subject-matter. Actually, in these circumstances, medium becomes integrated as part of subject-matter, making the artist’s statement more complex and elusive to the viewer.

One can see the emotional impact of technical approach in a comparison of two details below: Van Gogh employs virtuosic brushstroke (Fig. 7-3) in his Peasant Girl of 1890, inviting us into the passion of his creative process; while Thomas Eakins’ Addie (Fig. 7-4), painted ten years later in the U.S., evokes empathy principally with the pensive subject of his portrait.

Marcel Duchamps’ Stair Nude Descending case (Fig. 7-11, 1912) offered a new paradigm for treatment of the nude human figure, creating distance based on a photographic time-lapse model.

Technique, however, is but one of a number of factors that could effect our perception-of and reaction-to these two portraits. It is possible that our emotional filters are far more complex than we have realized.

For example, there is a strong likelihood that the sunny, outdoor palette of the Van Gogh painting attracts us to his subject more readily than the somber color-scheme of the Eakins. Warm color usually stimulates a feeling of empathy; cooler color seems to induce a sensation of distance.

Additionally, when a study such as Eakins’ Addie is “life-like,” we relate rather more easily to a “sentient person,” than to spontaneous brushmarks on the canvas. Exaggerated handling of a medium often creates psychic distance, despite revealing the artist’s emotion. Verisimilitude, on the other hand, typically elicits the empathetic response of the familiar.

Of course, there is no “one size fits all” predictor of just what will create “connection” between viewer and art-work. Nor is there assurance that what affronts one person (creates distance) may not have an opposite effect on someone of another generation or culture. Having offered that caveat, however, I will venture out on a limb and suggest a few aspects of art-work that typically appear to stimulate empathy and psychic distance among viewers. Then we shall test them by observation of a few representative works.

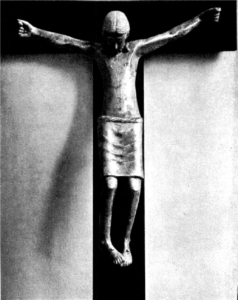

An illuminating contrast of some of these psychological factors occurs when we study two relatively contemporary religious icons dealing with the Crucifixion. Christian theological issues may impinge on one’s judgment of the efficacy of one or both of these works, but theology aside, we should be able to see how the artists have addressed the poignant emotion involved.

In Fig. 7-7 (Crucifix, 23 in. high, Bronze) by Gerhard Marcks, the figure appears to be in repose, as in death. The onlooker is not implicated in any visceral reaction to physical extremes suffered in the “completed” dying process. Physical characteristics are reduced to a minimum, and the Passion of Christ is understated to provide the viewer with significant psychic distance.

Contrast then the portrayal by Charles Umlauf (Fig. 7-8, Crucifixion, Bronze) which appears to portray Christ in the moments prior to his death, still in the throes of a life-and-death struggle.

Whistler’s Portrait of Miss Alexander (Fig. 7-12 ) combines distance from geometric design elements and virtuosic style with empathetic character study

Contorted and emaciated, the Umlauf Christ embodies conscious distortions, such as the conspicuous enlargement of facial features and hands — the locus of human sensation and connection. Muscular tension is palpable as the figure appears almost to wrest his extremities from the cross.

From a theological point-of-view, the two treatments of this pivotal Christian event would seem to juxtapose a symbolic remembrance (Marcks) against a psychologically painful reenactment (Umlauf). The presumption of sentience (life) creates a radically different psychological environment for the viewer.

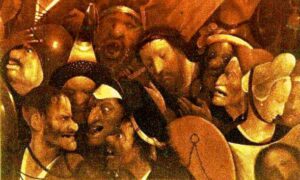

We see profound psychological awareness in two other treatments of the Crucifixion drama, this time painted rather than sculptured. Bearing of the Cross (Fig. 7-9, below, 1505-10) by the Northern (Flemish) artist, Hieronymus Bosch, creates an emotional holocaust around the central image of a spiritually-centered Christ figure. Excepting St. Irene, who looks away grieving, faces of madness surround a Christ whose cross, in this case, does not appear physically burdensome. Rather than attempting to portray an extraordinary Being, Bosch sees him as “fully human” in a sea of mad dogs.

The mysterious and elusive Italian Renaissance painter, Giorgione, sometime before his disappearance from Florence in 1516, also painted an image of Christ Bearing the Cross (Fig. 7-10, below). Evidently painted from a contemporary model, the figure seems chosen for his even features, and aside from an almost furtive sideways glance, does not betray complex emotions traditionally associated with the grueling Road to Calvary. Perhaps influenced by a Mediterranean (Classical) ideal of physical perfection, this Christ appears to carry an apocryphal Cross, a physical burden we are not asked to share. Bosch employs shrieking assailants to create empathy for his Christ, while Giorgione invokes Praxitelean calm to distance his figure from roiling crowds.

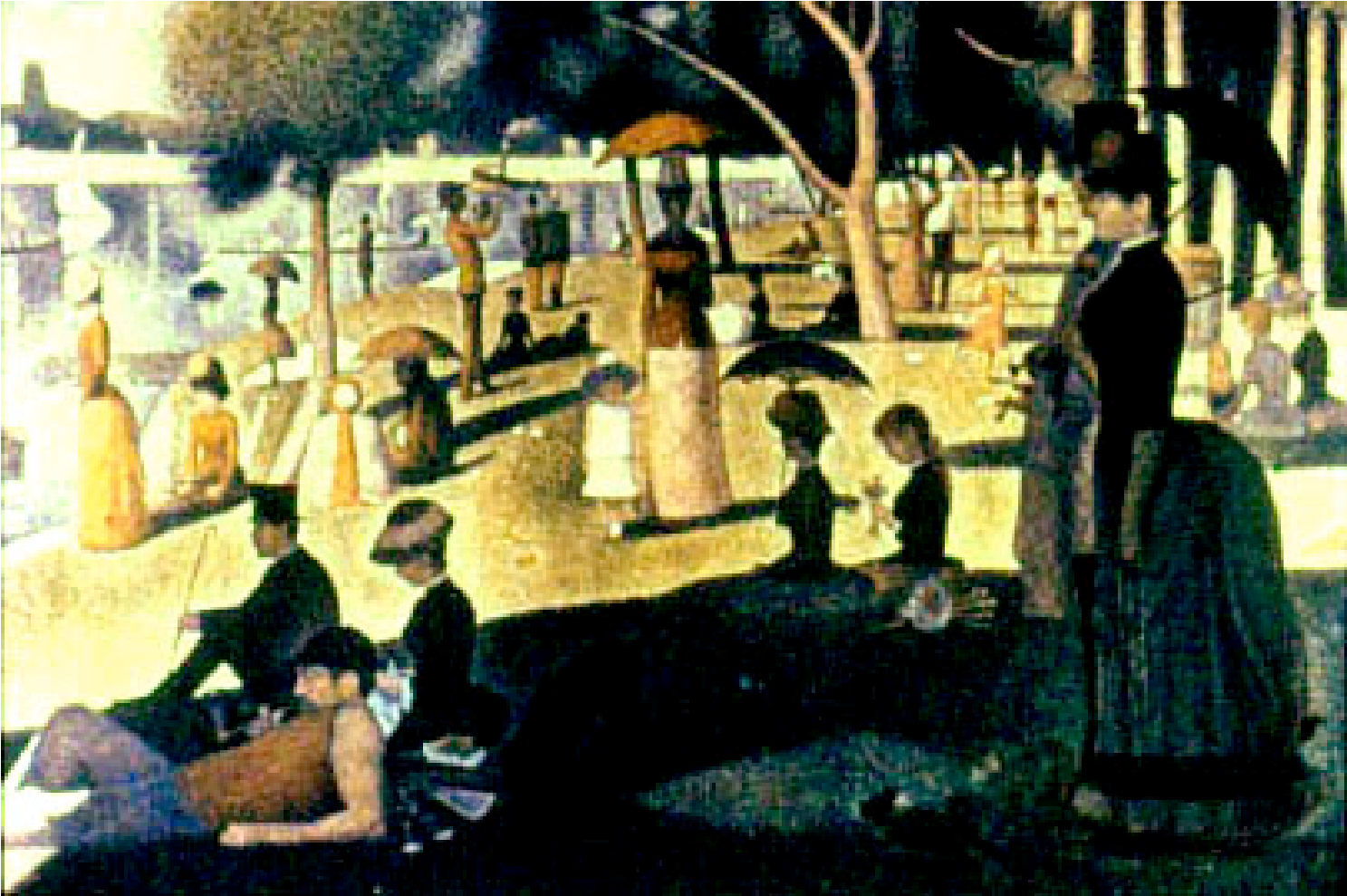

In a technical approach to creation of psychic distance, the French painter, Seurat, synthesized form from cascading dots of pigment in The Bridge of Courberdie. (Fig. 7-13, 1885-86 )

is not difficult to see that this tension between empathy and psychic distance indeed harkens back to that dichotomy alluded to earlier in this discussion of human creativity — between what the Greeks differentiated as “Apollonian” and “Dionysian” impulses. That is to say, there seems to be an innately human urge to “feel” and to “express” (Dionysian) which manifests in psychological terms as empathy. And over against that impulse (thus limiting it), we find an equally human need for “order,” which manifests as psychic distance or the triumph of mental control over raw emotion.

The 20th century embraced a potent tool in the quest for Apollonian distance, the power of abstraction. Known to artists for millennia, this language gained mainstream acceptance with the evolution of Cubist style in the opening decade of the 20th century. Technical innovators of the previous generation such as Manet, Cezanne, and Seurat in France and Whistler in Britain had already paved the way by breaking down the fabric of visual reality into elements of color theory, retinal mixing of pigments, and analytical form.

An eloquent spokesman for the Victorian Age (though one, ironically, who railed against it’s conservatism) the American expatriate, James McNeill Whistler (Fig. 7-12) spent most of his turbulent career in Great Britain. Considered a radical by most of his contemporaries because of his brash technique and unorthodox subject-matter, Whistler today is capable of touching his audience with the warmth and empathetic rendering of a portrait subject. Comparison of his Portrait of Miss Alexander with the Duchamp work of a generation later suggests Whistler’s delicate emotional chemistry with the socialite before his easel.

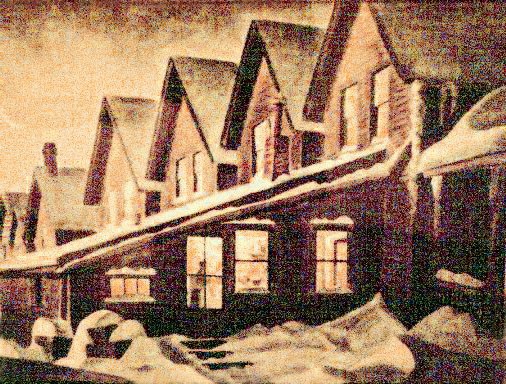

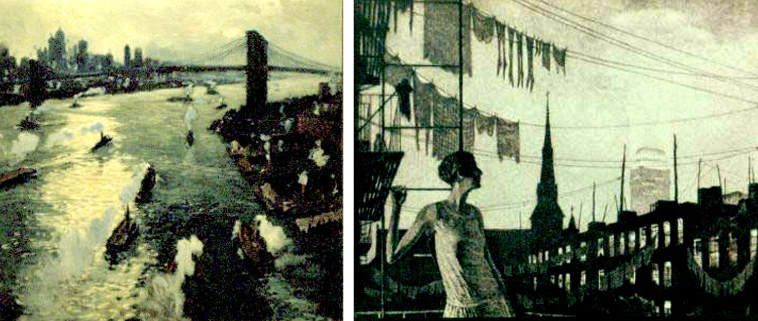

Bellows’ Henri’s The Lone Tenement, (Fig. 7-18, left/ 1909) and Snow in New York (Fig. 7-19, right/ 1902) present “mixed” psychological stimuli, tastefully reflecting less than-glamorous aspects of typical urban life in America.

Just as Whistler’s images had increasingly vanished in a welter of atmospheric effects, the French artist, Seurat, found his metier in a technique which came to be known as “Pointalism” (Fig. 7-13). Preparing the way for Braque and Picasso’s assaults on “rational” form, Seurat dissolved bridges, sailboats and hillsides into almost-holographic symbols of optical experience.

Often, the most interesting and satisfying psychological statements in art are sufficiently complex that they will have substantially different impact on divers people.

Duchamps’ noted Nude Descending a Staircase, for example, creates distance from the nude figure by reducing the human body to a series of relatively inorganic shapes which seem to have their genesis in slow-motion photography. But one is inescapably drawn to kinetic excitement of planes flashing across a darkened ground, and the artist’s warm, earthen palette likewise invites an empathetic response from the viewer. It is ambivalent stimuli such as these that help make specific works of enduring value.

An American painter capable of this level of psychological complexity is Thomas Hart Benton, whose work, Cotton Pickers, (Georgia) is illustrated in Fig. 7-14. Benton saw pathos in physiques and body-language of Southern cotton-pickers not-unlike that which the 16th-cen. painter, El Greco, imagined among Money-changers driven from the Temple by Jesus. Attenuated limbs and postures of resignation appear part of a choreographic program calculated to “hook” the viewer. Neither painter offers enough specificity, however, to maintain our emotional connection, and both Benton’s intricate plastic design and El Greco’s ecstatic color provide psychic distance we need to balance their pathos.

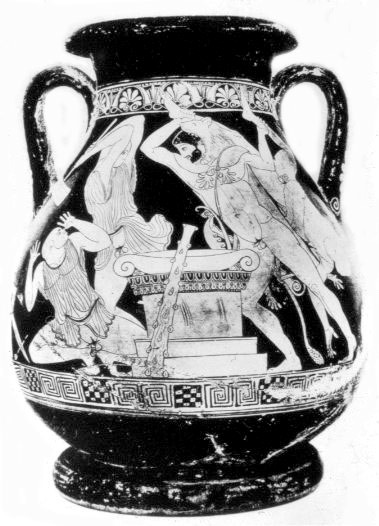

Greek clay treatment of erotic theme ( Fig. 7-21, 480 B.C.) relies on “archaic smile” for emotional relief.

Seurat, interestingly, offers an antithetical varient on the empathetic language of a Benton or El Greco with his Sunday Afternoon at the Grande Jatte (Fig. 7-16), painted in 1884-86. “Apollonian” strollers or sunbathers in the park more nearly resemble chess pawns than a rollicking bourgeoisie (compare Fig. 7-17 by American painter, John Sloan, for example), though the warmth and human content invite our interest. Sloan, more than a generation later, chose a gregarious naturalism rather than further deconstruction of Seurat’s geometry into Cubism.

Two views of New York City from the time of the “Ashcan School” rely on mixed psychological signals to deliver enduring portraits of complex reality. Robert Henri’s 1902 Snow in New York (Fig. 7-19) uses a cool, almost-monochrome palette to describe a bleak uptown street, but relieves the psychic distance of the urban canyon with warm “spots” associated with human activity.

Another interpretation of New York life, The Lone Tenement (Fig. 7-18, 1909) by George Bellows (whose viewpoint was anything but bourgeoise), depicts squalid figures huddled around a fire considerably removed from the viewer (psychic distance), while simultaneously describing a desolate part of Manhattan in warm earthen tones (empathy) usually found in scenes of New Mexico. Neither artist would have relished any hint that they sought to romanticize urban life or its meager pleasures, but both couched their “realism” in ambivalent terms allowing the viewer “selective” feelings.

Indeed, psychological “ambivalence” — leaving the door open for complex levels of interpretation by the viewer — may be one of the hallmarks of “mastery” in the arts. A work that leaves no questions is hardly one the viewer must revisit repeatedly.

Contrasting treatment of erotic theme by French master, Maillol ( Desir e, Fig. 7-23, 47 in. high. plaster) fails to achieve emotional synthesis of Olympia Master’s Prince of Centaurs and Lapith Bride (Fig. 7-24, Greek Temple at Olympia, 470456 B.C., opposite page), where detachment of figures lifts psychic burden from viewer.

Take, for example, two sculptures by 20th-cen. masters of German origin: Ernst Barlach and Georg Kolbe. Barlach’s work typically was small woodcarving, because he worked covertly under scrutiny of Nazi authorities offended by his Jewish heritage. (German woodcarving tradition had been strong since Medieval times, with a penchant for expressing subtle emotional states—e.g. Tilman Riemenschneider 1460-1531).

From a psychological standpoint, Barlach’s Singing Man (Fig. 7-20) elicits empathy as a result of tension in arms pulling against a raised leg, and the kinetic “rocking” motion implied; but the impassive face belies levity (see Fig. 2-42) and leaves the viewer wondering if this could as well be the lament of a grieving soul. In this instance the work is bronze, and its small scale and minimal detail contribute to an enduring quality of distance that merits repeated visitation.

Kolbe’s work (Frauenraub, Fig. 7-22) is likewise convoluted in psychological terms: its title suggests the theme of an abduction, making emotional connection with the viewer immediate. But the artist confounds our angst with almost balletic entwinement of the two bronze figures, a complete absence of tension or expression in the faces, and a “formal” (plastic) unity of arms and shoulders which make the two figures almost as one. (I have used the term “whole-consciousness” before, to suggest a perceptual rather than a conceptual bonding of parts into a larger totality.) Kolbe manages to leave us free of the burden of witnessing a violation here by the alchemy of his rhythms and his almost Classical dispensing with melodrama.

A dramatic contrast in outcomes is seen below, an “early” work of the French master, Maillol, entitled valiant effort to counter Desire (Fig. 7-23, plaster relief, 1904). His pathos with strong plastic geometry (heraldic balance of forms) is defeated by the temporal quality of gesture and body language. Insufficient distance leaves the viewer feeling prurient rather than ennobled.

California artist Jack Zajac transmutes impaled lamb into a metaphor of the Crucifixion (Fig. 7-25, Bronze) expressing empathy with medium providing a measure of psychic distance.

One might also compare the handling of an attempted abduction by the anonymous, 5th-cen. Greek sculptor at Olympia (Fig. 7-24, 470-456 B.C., Marble). Despite encroaching melodrama (pathos) in Red-Figured pottery decoration, starting as early as 530 B.C. (Fig. 7-26, 470-460 B.C.), the Olympia artist chose profound propriate to monumental Temple sculpture.

The poised Lapith Bride exemplifies Apollonian order amid chaos, much as Zajac’s Easter Lamb above (Fig. 7-25, Bronze) becomes a 20th century restatement of the Passion of Christ.

Certainly the subjective factor in appreciation of any work of art argues against blanket assertions that a particular work is or is not successful. But the factor of psychological impact is coercive enough that arguably one might be justified in talking about a work “missing the mark” in its appeal to human emotion.

Unrelieved tension which is not adequately offset by “reduction” in some (redeeming) aspect of medium, plastic content, color or execution may be said to “lack adequate distance.” (Fig. 7-27, Despair, Hugo Robus, 1927) And conversely, a work which is almost totally devoid of empathetic value, either in subject-matter or in resourcefulness of expression, generally fails to make a lasting imprint on the consciousness of the viewer.

Despair by Hugo Robus (Fig.7-27, Bronze, 1927 ) offers little to counter overpowering empathetic impact on the viewer.

Thus, two works shown above, though worthy essays, would seem to resist repeated encounters by the average viewer, due to unrelenting visceral stress on central figures. In Fig. 7-28, Cross Bearer by Hans Schwaighofer (wood/1961), gravitational strain on the crouched figure quickly becomes unsustainable for the viewer. And in Kathe Kollwitz’ Home from Market (Fig. 7-29, charcoal drawing) the medium fails to transmute a depressing vision of domestic exertion into one where the redemptive power of light or color gives the viewer a small window of psychic escape.

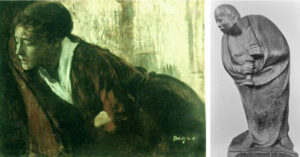

For contrast, compare a Degas painting entitled Melancholy (Fig.7-30, 1874) with a Barlach figure, Man Alone (Fig. 7-31, 1911) — both evidently dealing with human despair. Degas’ melancholic subject appears in a sweeping warm diagonal punctuated by translucent white sunlit curtains and a brilliant collar echoing the shape of her face. Unfortunately, the warmth of Barlach’s wood is lost in reproduction, but beyond that, no aspect of the carving offers gratification to eye or plastic consciousness to balance pathos of the unsteady figure.

Edvard Munch chooses a complex secondary color-scheme fraught with tension to enhance his image of Melancholy (Fig. 7-32, 1894) as two background figures (a metaphor of jealousy) appear mysteriously on the horizon.

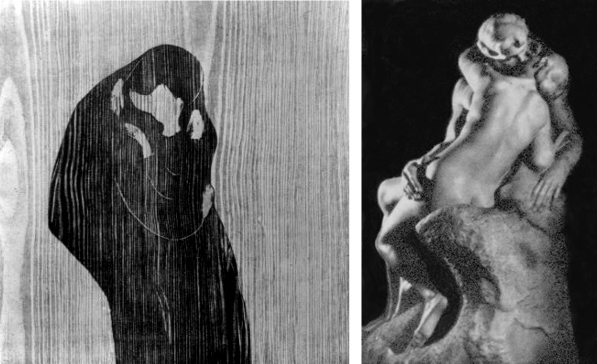

Medium often becomes a critical factor in distancing subject-matter that is emotionally charged: Edvard Munch chose a print on wood grain for The Kiss (Fig. 7-33, 1902), with a minimum of empathy. In contrast, Rodin created a life-like Marble image (The Kiss, Fig. 7-34) with polished surface to further enhance its sensuous effect.

Luminesence and warm palette relieve pathos in Degas’ Melancholy (Fig. 7-30, left/ 1874), in contrast to Barlach’s Man Alone (Fig. 7-31, right, wood/ 1911), which invites unremitting empathy unmediated by strong plastic interest.

Avoiding Rodin’s emotioncharged representation of nude, embracing figures, Romanian sculptor, Constantin Brancusi, carved two box-like forms with “wooden” appendages grasping each other (The Kiss, Fig. 7-35, 1910) — a vision of human passion so tempered with aesthetic distance that it obviously was never intended to elicit an erotic response. Like his portrait of Mlle. Pogany (Fig. 2-2), Brancusi’s The Kiss offers only an archaic geometry to define a sublime human metaphor, leaving the viewer to react with humor, with wonder or with a shrug.

Thus, it appears there is an apt psychological proportionality: the more pathos, the greater need for a balance of artistic language, style or medium. Kissing clearly works better as television than it does as monumental stone sculpture. Rodin could be the ultimate exception.

Perhaps it is light, however, that provides visual artists with their principal psychological tool. With it, the graphic artist or painter can etch strength or weakness, love or hate, avarice or compassion on a human countenance, and the museum curator can transform a sculptured image from passive to aggressive or from heroic to pathetic. In theatre, light becomes the sine qua non of many profound dramatic situations, and in the hands of a master, often becomes a central member of the cast.

In the two works above, light goes beyond mere creation of mood, to transform the ethos of an urban setting into something almost mystical. In both instances, an artist virtually eschews color in favor of a “pure” light which appears to transmute gritty reality into one fraught with idealism.

Pervasive tension in color and form is tempered by strong plastic arrangement “supporting” Munch’s stoic figure in Melancholy (Fig, 7-32, 1894).

Josas Lie uses oil paint in Path of Gold (Fig. 7-36) to describe an irridescent ribbon of light traversing a dingy river on the threshold of New York City. An inhospitable city (distanced) becomes suffused with a warm (read empathetic) ambiance, much as does the Manhattan of Martin Lewis in The Glow of the City (Fig. 7-37, etching/1930). For both artists, light is a vehicle for transcending mundane reality.

The fashion in which light is entwined with the American psyche may show up most forcibly in works which meld the “vernacular” subject-matter of early 20th-cen. Regionalism (Figs. 7-38 and 7-39) with remembrance of war and economic depression. As with the style we call Luminism (Fig. 7-43), which was born roughly a century earlier, American artists have often rendered “darkness” the more eloquent by focusing mainly on ephemeral aspects of light rather than sensuous color. Both Hopper and Burchfield here cast us in the role of “outsiders,” confronting the shadowy familiarity of typical American space, yet knowing the discomfort of feeling excluded.

Light functions as an empathetic catalyst in Lie’s Path of Gold (Fig. 7-36, left ) and suffuses the New York of Martin Lewis in his etching, The Glow of the City (Fig. 7-37, right 1930). American artists of the 19th and 20th centuries in many cases exhibit a strong affinity for light as an expressive psychological tool.

The American painter, N.C. Wyeth, often mistakenly delimited as solely an illustrator (Fig. 7-40), helped formulate the Brandywine tradition’s love-affair with cool, outdoor light, prior to his untimely death in 1945. His son, Andrew, developed a sophisticated Tempera style based in large measure on an intimate circle of people and places described with Transcendental vision (Figs. 7-41 & 7-42) that speaks as much about Quaker leanings of the artist as it does about idiosyncratic friends in rural Maine and Pennsylvania. (See Chap. 10.)

While light may profoundly effect our psychological “engagement” with visual images of Hopper, Burchfield, the Wyeths (and other Masters of Chiaroscuro: for example, Daumier, De La Tour or Vermeer), it can also be a factor in making the sudden leap from “rational” to “irrational” imagery. A discussion of that leap will lead us into the realms of Fantasy and Surrealism — but only after we have reckoned with problems of “Realism” and “Reality” in Chapter 10.

First, however, there is a necessary digression to more fully explicate the roll of process in creating sculptured or painted images. The process with which an artist chooses to execute his or her idea in its final, “public” form (ie. a painted or sculptured object) virtually determines many outcomes of the creative endeavor. These practical choices also give us significant insight into the artist’s personality.

Thus, our next focus will be to treat sculpture more intensively as an art form in Chapter 8, followed by a closer look at painting process in Chapter 9.

Eerie coastal light of Martin Heade’s Approaching Storm, Beach near Newport (Fig. 7-43, 2nd-half of 19th cen./ left ) may anticipate 20th-cen. Surrealism, while Vermeer’s 17th-cen. work, A Woman Weighing Pearls (Fig. 7-44, ca. 1664/ right) is strangely hallowed by its almost metaphysical illumination from a nearby casement.

Fig. 7-2. Manet strokes paint on canvas broadly and in defiance of canons of illustrative propriety (Ball Scene, detail, 1873,) in much the same disconcerting manner seen in the Kollwitz self-portrait (Fig. 7-1).

Portrait details by Van Gogh (Fig. 7-3, Peasant Girl, 1890, above) and Thomas Eakins (Fig. 7-4, Addie, 1900, top) illustrate different approaches to creating empathy and psychic distance.

Crucifixions by Gerhard Marcks (Fig. 7-7, Bronze, top) and Charles Umlauf (Fig. 7-8, Bronze, above) contrast means of attaining distance and empathy in sculpture.

Empathy for Bosch's Christ (Fig. 7-9, Bearing of the Cross, top) evolves from a "Northern" focus on bestiality of those around him, while the psychic distance implicit in Georgione's Mediterranean idealism (Fig. 7-10, Christ Bearing the Cross, above ) is evidenced by placid features and absence of visceral tension or craven onlookers.

Sources of EMPATHY

- Exaggeration

- Distortion

- Unresolved tension

- Warm color

- Verisimilitude

Sources of PSYCHIC DISTANCE

- Understatement

- Plastic Content

- Aesthetic emphasis (medium)

- Cool color

- Reduction (abstraction)

Benton's Cotton Pickers (Georgia), Fig. 7-14, top, creates empathy much as does El Greco's Christ Driving the Money-Changers from the Temple (Fig. 7-15, above) with body language and choreographed tension.

Formal geometry replaces naturalism to "distance" Seurat's bourgeoisie in Sunday Afternoon at the Grande Jatte (Fig. 716, top, 1884-86). John Sloan chose empathy in his South Beach Bathers of 1903 (Fig. 7-17, above) which achieved temporal effects through anecdotal gesture.

Both Singing Man by Barlach (Fig. 7-20, top, Bronze,1930) and Frauenraub by Georg Kolbe (Fig. 7-22, Bronze, 1916, above) weave distance and empathy into tightly-knit psychic fabric.

Pathos of contemporary Red-Figured Pottery design (Fig. 7-26, top) contrasts sharply with detachment of monumental sculpture style from Olympia (Fig. 7-24, above ).

Unremitting stress may create discomfiting psychology in works such as Cross-Bearer (Fig. 7-28, top, wood, 1961) by Hans Schwaighofer, or Kathe Kollwitz' Home from Market (Fig. 7-29, above, charcoal c. 1944).

Early 20th-cen. treatments of The Kiss contrast "distanced" wood-block print (Munch, Fig. 7-33, 1902, left) and humorous, "cubed" lovers of Brancusi (Fig, 7-35, stone, below) with lifelike, 19th-cen. Marble rendition by Rodin (Fig. 7-34,right).

Brancusi invokes ancient Assyrian frontality (Fig. 7-35, 1910 ) to wrest intimacy from stone rendering of The Kiss.

Edward Hopper's Seven A.M. (Fig. 7-38, 1948) juxtaposes prim storefront with primal vegetation in metaphoric nexus of good and evil.